Cynicism Is the Enemy of Action

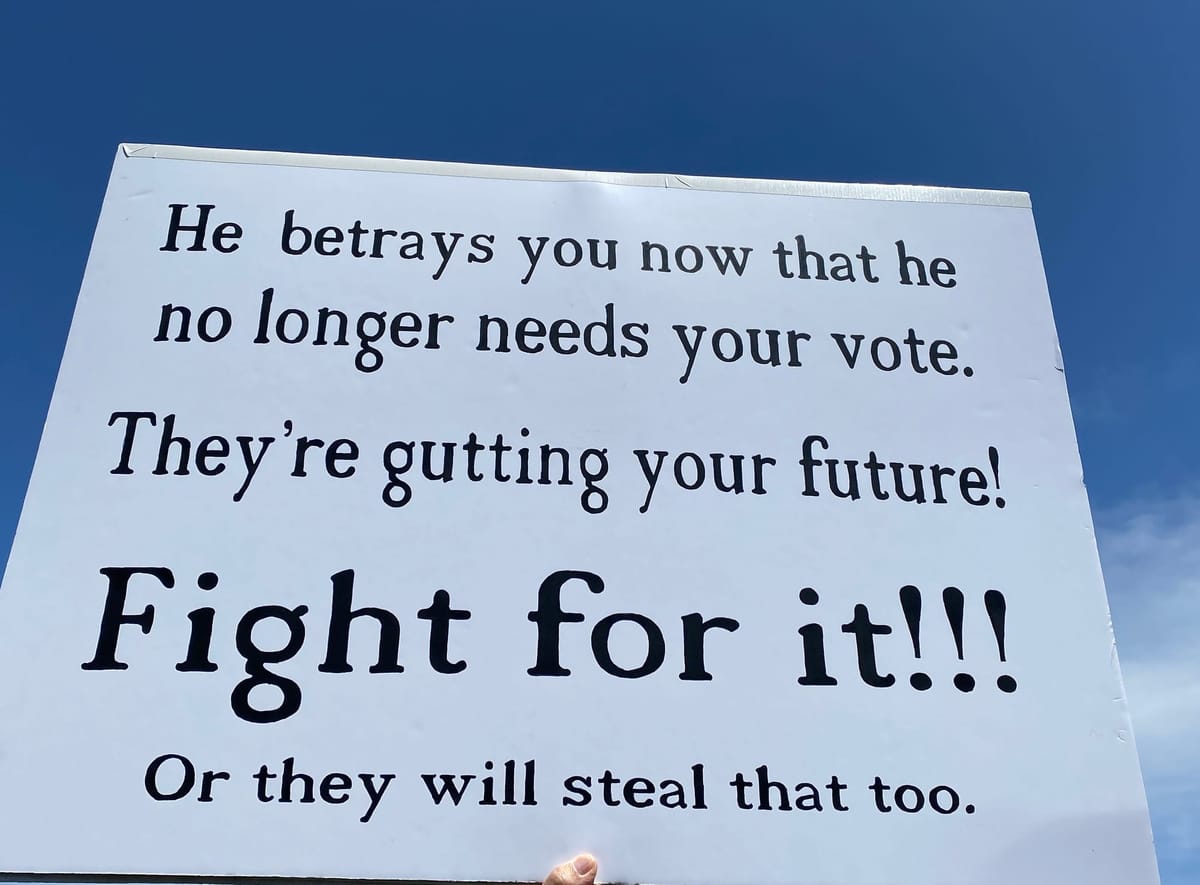

We have distant enemies, the enemies of truth, justice, human rights, and environmental protection, and they are easy to recognize and oppose. We also have near enemies, the cynics and defeatists among us who in theory agree with our goals but in practice are forever sabotaging them by insisting that we cannot achieve them and we are naive to try. In fact they often dispense more scorn and hostility on those who are trying than on the actual enemies. They've been around all my activist life, and they piped up in a big way the morning I'm writing this, to inform me that Maine's Senator Susan Collins would never vote no on the Big Bad Budget Bill, as I urged people to call senators, which means they were also urging people not to bother. In theory they were slagging Collins (who is, yes, a terrible person), but in effect they were slagging and undermining people working for that no vote.

Collins did vote no, and I assume that she did because of pressure from constituents calling and writing, from non-cynical people who did something because they had not assumed the outcome. When you don't assume the outcome, you recognize that you may be able to participate in shaping it; perhaps more participants might have further determined the outcome, which was decided by one tie-breaking vote from the vice-president. That is the most basic tenet of hope, that the future is being made in the present, does not yet exist, and committing to it means a shrugging off of all the false prophets who as cynics, defeatists, and even optimists pretend that the future has already been decided. All these are postures from the sidelines, and they are postures that excuse and justify being on the sidelines, which is maybe their real agenda.

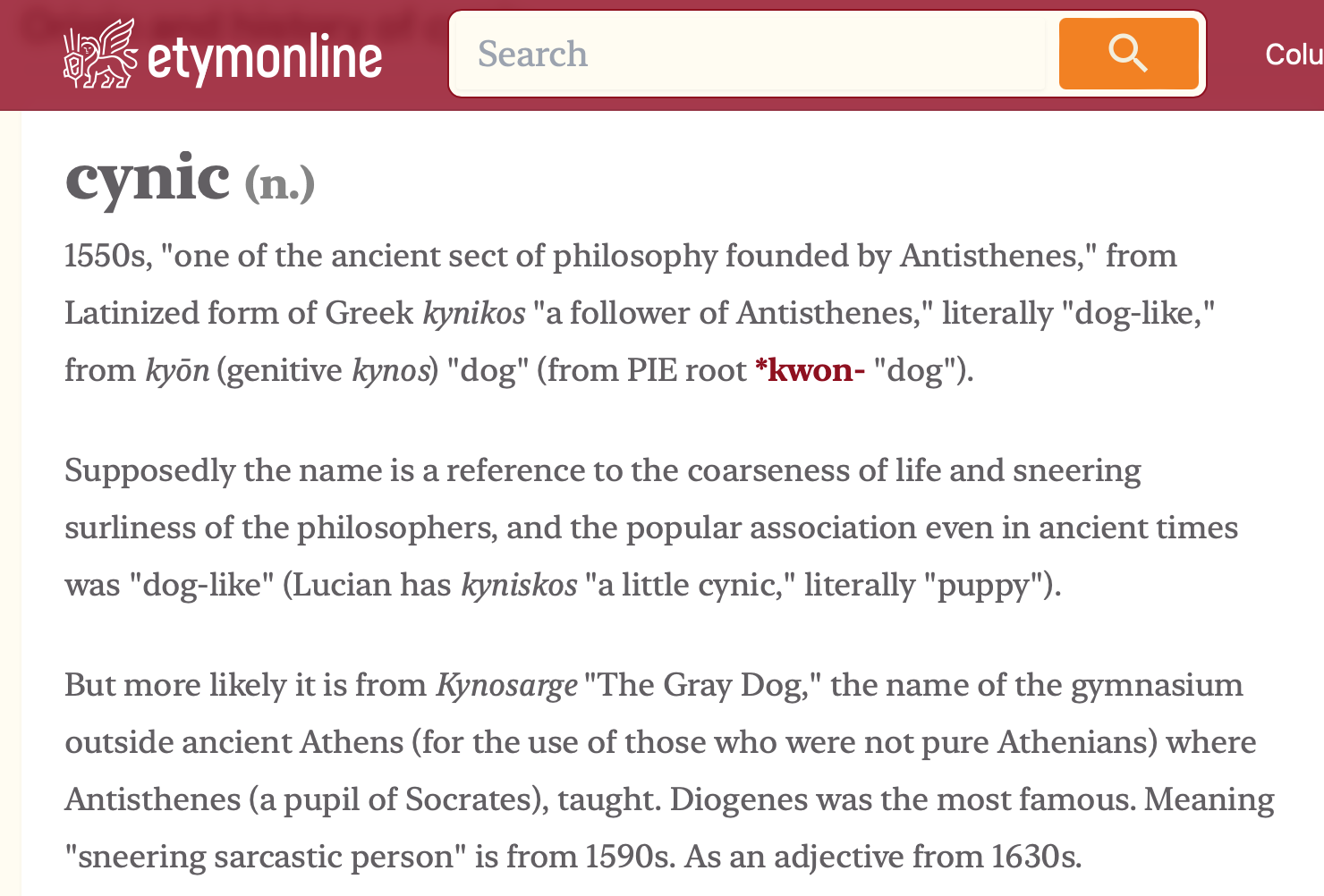

This is the most dire moment in the history of the United States and no one should be on the sidelines, and no one shoudl be undermining those who are showing up for justice, human rights, and environmental protection. There's a remarkable passage in the (highly recommended) book Let This Radicalize You by Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba. They write, "As you develop your tactics and strategize, it’s important to be aware of the pervasiveness of cynicism among many of those you may be trying to reach. Cynicism is a dominant force in today’s political discourse, with some good reason and a favorite approach of the world’s political hobbyists." They quote another writer, Eitan Hersh, who calls people who follow and comment on politics without really participating "political hobbyists" and Kaba and Hayes continue: "It is important to understand the distinction between activists, organizers, and political hobbyists. Such hobbyists will often have very strict political standards, either around respectability or radicalism, to which few activists ever seem to rise. If you organize anything political, you are likely to attract the criticism of hobbyists, since for some people, critique is a pastime. Of course, organizers make genuine mistakes that political hobbyists may react to, but the fact is, making mistakes is a consequence of trying. The more you take action, the more errors and missteps you will make along the way. A person who has attempted nothing can easily point to the fact that they have never failed, but what have they built? What have they healed?"

I think back to the phrase climate journalist David Roberts coined a decade ago, the "doing it wrong brigade," for those people on the sidelines who tell those who are doing the work that they should be doing it differently, criticizing their tactics, goals, alliances, or some other thing that falls short of perfection since as Hayes and Kaba point out, when you're not doing anything you can set impossible goals and then lounge about figuring out how those doing the work fall short. Roberts was specifically talking about the long campaign to stop the Keystone XL pipeline, the pipeline that would've further aided cheap transport of the some of the dirtiest crude oil on earth, Alberta's tar sands sludge, to refineries and ports in the United States.

He wrote in 2015, when Obama had finally come out against the pipeline--before Trump would reverse that decision, putting the fate of the pipeline in play for another four years before Joe Biden killed it decisively soon after taking office. The campaign to defeat the pipeline took a decade, and the whole time it was unfolding, cynics and Doing It Wrong Brigade members were attacking those who did the work that eventually led to this landmark victory. As Roberts and environmental journalist HR Smith both observed, the people on the sidelines were very fond of the argument that this was the wrong campaign, the wrong cause, because stopping the Keystone XL wouldn't stop all climate emissions everywhere forever. Roberts notes, "t is also ludicrous to imagine that the primary goal of climate activist campaigns is to reduce emissions. It would be like criticizing the Montgomery bus boycott because it only affected a relative handful of black people. The point of civil rights campaigns was not to free black people from discriminatory systems one at a time. It was to change the culture."

Smith wrote way back in 2013, "Last week, the political writer Jonathan Chait wrote a short piece for New York magazine titled 'The Keystone Fight is a Huge Environmentalist Mistake.' Others have already well rebutted the argument and summarized the debate. What I would add is that Chait has provided us with an excellent example of what I have come to think of as One Ring syndrome." That is, that each and every bit of activism should identify the One Ring to Rule Them All--yes, from Lord of the Rings--and then drop it in Mount Doom, saving us all forever, and that anything that took on anything that wasn't the One Ring was taking on the wrong cause.

Winning the Keystone XL campaign was not going to hugely reduce global carbon dioxide emissions. But it did a ton of other stuff that mattered greatly. It educated a wide swathe of the public about the role of pipelines in the fossil fuel industry and their dangers--they all too often break, leak, contaminate, as well as about the Alberta Tar Sands and their threat to the planetary future. It created or supported many coalitions, including with Native Americans and rural people, including farmers, in the areas the pipeline would pass through, and created gorgeous coalitions between those directly impacted communities and the larger climate movement. It inspired others to take on and defeat other pipelines or support other pipeline campaigns. It helped the climate movement grow. It put the industry on notice that they wouldn't always get their way, and trying to do so might prove slow and expensive. And then we won the actual battle. Keystone XL was and is dead.

In 2012, around the same time that the Keystone XL battle was joined, Bill McKibben wrote a hugely impactful Rolling Stone article, Global Warming's Terrifying New Math, about the unburnable carbon--if we were to keep from cooking the planet--that the fossil fuel industry was intent on extracting and sending out to be burned. The essay and the work McKibben did with 350.org and other climate groups launched the fossil-fuel divestment movement, which was met early on with much the same kind of criticism the Keystone XL campaign was: that it was the wrong goal, that it was ineffectual, that it would fail.

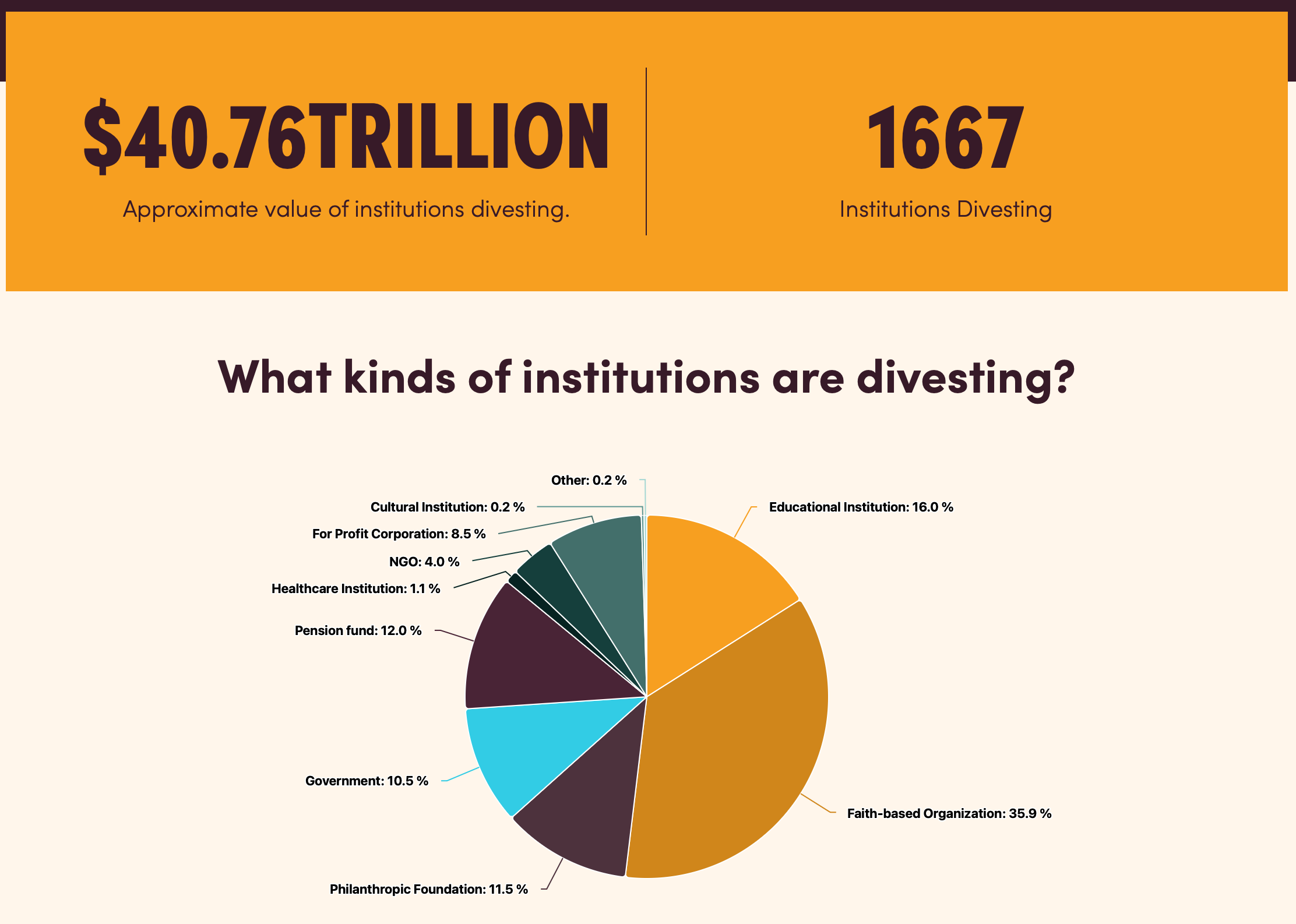

So far more than forty trillion--that's TRILLION, not billion--dollars (or their equivalent, it's a global movement) has been divested. And as with the pipeline campaigns, much of the impact wasn't so direct and immediate. It created a way for people to recognize that many of us individuals and institutions with money in banks or investments were invested in the fossil fuel industry, that we were complicit, and that with our money we could vote to become less so. It created a way for students at universities with such investments to campaign and win and recruited many future climate leaders. It also portrayed the fossil-fuel industry as amoral and destructive. In other words, it created public awareness and shifted attitudes, which is less tangible than forty trillion dollars, but not necessarily less important.

I'm taking this detour through recent history, because the past instructs us about the present. All comparisons are partial, and what I'm comparing with these examples of the Keystone XL pipeline and divestment campaigns is how despite attacks from the sidelines they succeeded, and they succeeded in indirect ways that the critics seemed unable to apprehend, as well as in direct ones (and one thing you have probably noticed is that the people prophesying defeat almost never come back to admit they were wrong; usually they're off prophesying some new defeat instead). We right now are facing an immediate and colossal threat or more than a threat, since the harm is already happening, and we need to face it with everything we've got. The authoritarianism of the Trump Administration is daily sabotaging more rights and laws, getting more destructive and vicious, as it reaches for more and more power while seeking to disempower Congress, the courts, the Constitution, and alll of us.

Last week's horrific Supreme Court decisions further undermine our rights and the rule of law, and the attacks on immigrants and refugees continue to get more brutal, while a new attack on birthright citizenship and naturalized citizens is underway. If we do nothing, we will live in an authoritarian country, where the checks and balances guaranteed by the Constitution and the rights encoded in the Bill of Rights will become irrelevancies. Neither the judicial nor the legislative branch of government is going to defend democracy and the rule of law on its own. It is up to us to do what we can. And for us to do it, we need to learn to dismiss and reject the defeatism and cynicism of those on the sidelines.

p.s. "Near enemies" is a term in Buddhism for the emotions that seem close to good things but are not so good. For example, pity is a near-enemy of compassion. Jack Kornfield wrote about this: " The near enemy of compassion is pity. Instead of feeling the openness of compassion, pity says, 'Oh, that poor person. I feel sorry for people like that.' Pity sees them as different from ourselves. It sets up a separation between ourselves and others, a sense of distance and remoteness from the suffering of others that is affirming and gratifying to the self. Compassion, on the other hand, recognizes the suffering of another as a reflection of our own pain: 'I understand this; I suffer the same way.' It is empathetic, a mutual connection with the pain and sorrow of life. Compassion is shared suffering. Another enemy of compassion is despair. Compassion does not mean immersing ourselves in the suffering of others to the point of anguish. Compassion is the tender readiness of the heart to respond to one’s own or another’s pain without despair, resentment, or aversion. It is the wish to dissipate suffering."

p.p.s. There are lots of reasons to hate Senator Susan Collins, if that's your thing, but I might note she also cast one of the votes in 2017 that prevented Trump's attempt to overturn the Affordable Care Act from passing (Senator McCain got to cast the dramatic final one, but Collins and Murkowski's no votes were why his no was decisive). Which doesn't mean that I love her. I'm interested in the acts and impacts, not the personalities.