Protect Our Neighbors: The Journey of a Sign

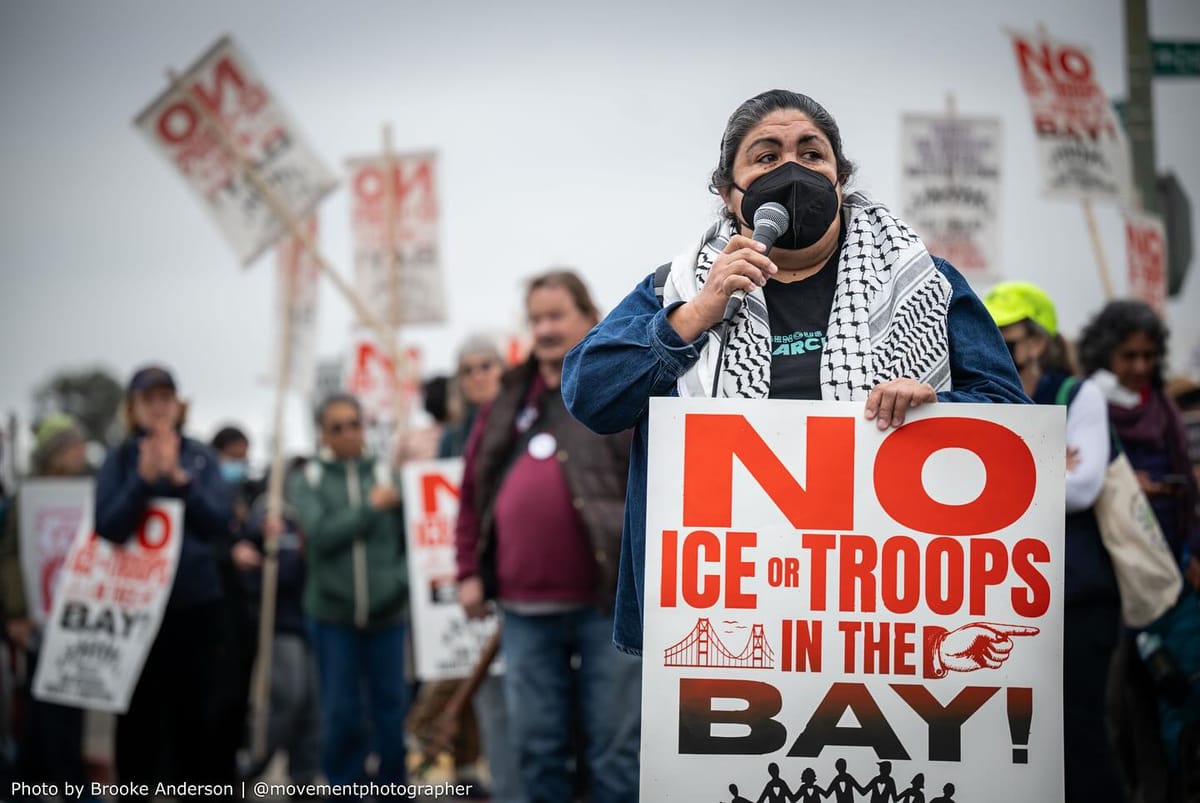

When word went out that border patrol agents had been sent to the Coast Guard island off Alameda near Oakland on the eve of October 23, Bay Area residents sprang into action. Before dawn the next morning, valiant locals began a blockade of the island, which is connected to Alameda by a single road, and they stayed all day. And at 5pm that Thursday, thousands gathered at San Francisco's Embarcadero – thanks to good organizing work, there was a plan and plenty of people knew about it beforehand. At both protests people sported large silkscreened signs that said "No ICE or Troops in the Bay/Protect Our Neighbors, Rights & Constitution." When I got to the Embarcadero myself I saw a few and then a few more and then they started to add up to a lot, not mounted on sticks but handheld.

Sure enough my brother David had set up a silkscreening station on a couple of wheeled tables right in the crowd, and was with a friend from Wisconsin printing away, and handing each fresh one to whoever was at the head of the line that had formed. (David has been making art for protests and demonstrations at least since the 1990s, and a lot of the posters and banners you're likely to see at a lot of Bay Area protests come out of his studio, often made with many volunteers and collaborators.) I watched them slide in a fresh piece of paper, lower the silkscreens, spread the marvelously gooey-gummy ink across them, and then lift the screen to reveal a brand new poster. They printed up and gave away well three hundred of them that evening, and of course I wanted one, with the thought I'd put it in my window. But the poster had another destiny.

I had a gig across town so I carried the still-damp poster with me and on the streetcar, and then back on foot I carried it across a parking lot, where the attendant took in the words, and beamed with – I'm not sure how to describe his expression, but there was joy, and maybe relief. He brightened and then beamed to see someone defending his rights simply by taking a stroll bearing the defiant language of the poster. He was a small brown-skinned man, and I'm not sure whether he was from Latin America or the middle east or some other part of the world, but we spoke briefly and I did my best to speak words of hope and possibility. Then we clasped hands in solidarity, but of course the poster did most of the work for me.

To think of him outdoors in public all day under these circumstances facing whoever and whatever comes his way is to contemplate what it's like to live in fear. It reminded me that most of us walk around being opaque, and if we're white who's to know where we stand on immigration? I wished I could convey my convictions so clearly all the time as I did walking down the street. Or rather most white people go around being opaque and most brown people walk around being aware they could be attacked, brutalized, grabbed, abducted, imprisoned, and deported, and being a citizen or a legal immigrant is no protection –Nicole Foy at Pro Publica reports that more than 170 US citizens have been seized and detained.

The encounter reminded me of one I'd had a few months earlier, when I was locking my bike up on Valencia Street in San Francisco, when a young woman came out of the pet hospital there and struck up a conversation (because she recognized me). We talked for perhaps five minutes, during which she told me that she was an immigrant from South Asia, and so frightened by this administration that she had deleted all her social media and withdrawn in other ways as well. That is, she had gone silent. Those of us who are comparatively safe – who are US born, who are white, who are straight and cis-gender – must be more outspoken, louder, more daring on behalf of those who cannot be.

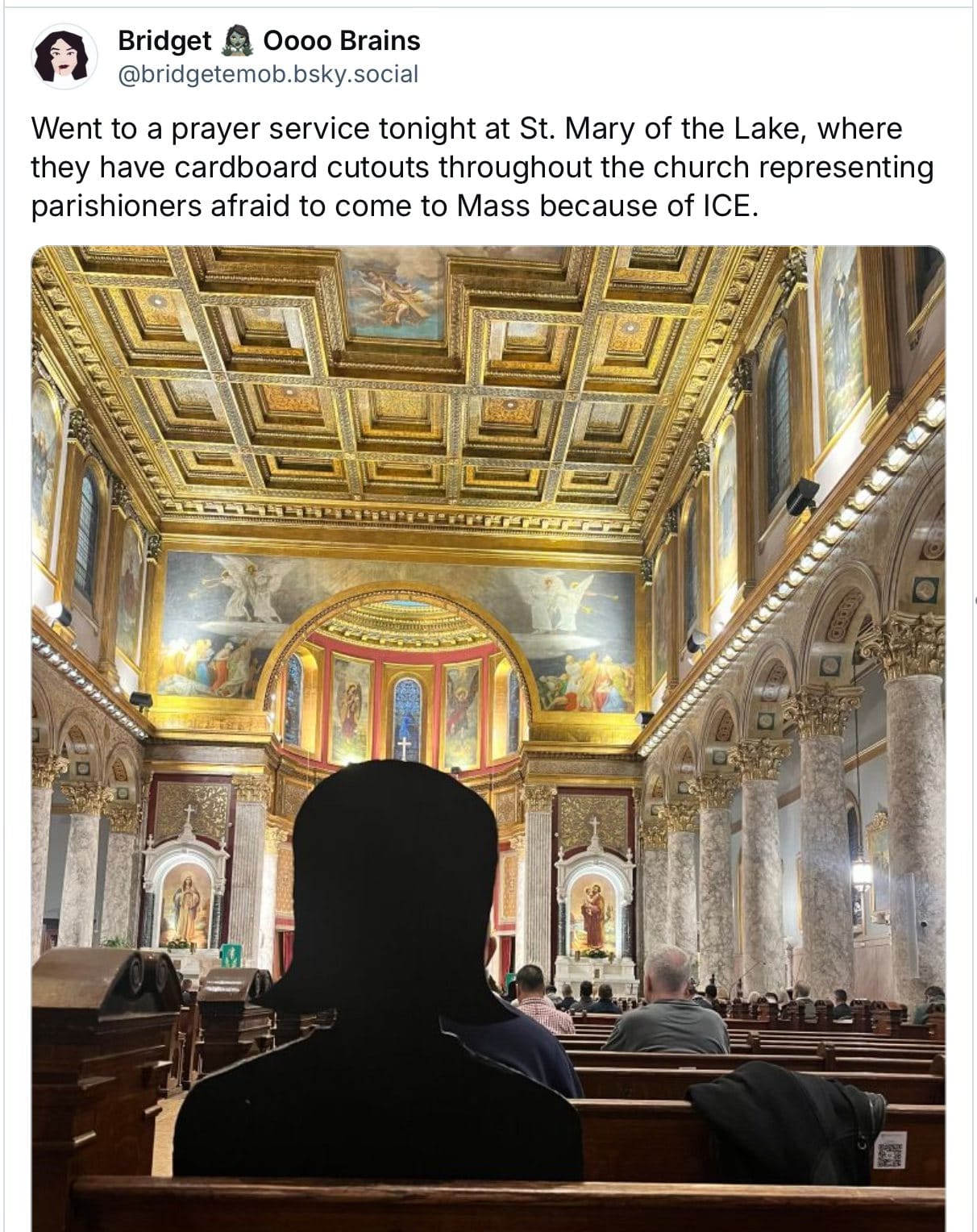

And we must remember how many people are now living in fear, afraid to speak, sometimes afraid to leave their home, afraid to go to work, afraid to walk down the street or go to the store or school. It's important to remember that lives are wrecked not just when they're actually seized by ICE, but when they live under the threat that this could happen to them, as tens of millions now are. Seized by fear, and act on it by giving up some of their freedom and confidence, some of their ability to participate in society as students or workers, as churchgoers and community members. Timothy Snyder famously wrote, immediately after the 2016 election, "do not obey in advance. Most of the power of authoritarianism is freely given. In times like these, individuals think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked. A citizen who adapts in this way is teaching power what it can do." But I would assume he means those of us who have secure status in this country, people like him, people like me (and while Snyder is now based in Toronto, he continues to speak up in the US). Power has taught immigrants, refugees, and those who resemble them what it can do.

Not long after that moment in the parking lot, I walked onto the stage with the person I was having a public conversation with, and we were greeted with polite applause, but when I propped up the poster down between us the applause became thunderous. It's often assumed that all political action is or should be trying to speak to either our enemies or to the authorities, that it is primarily a tool for making demands or converting the unbelievers. Sometimes and maybe often it is, but I believe that a major and maybe the most important audience is ourselves. It's where commitment and belief become visible and public, where we who live most of our lives in private become the public itself, become civil society, that force that regimes fear and history recognizes as an agent of change.

In other words, we are not primarily trying to convert those who do not agree with us; we are trying to reinforce and rally those who do. We have enough and more than enough people on our side: the job is not to recruit people to our worldview but to recruit them to action. In the current situation, we – the we who believe in human rights, climate action, justice, science, the rule of law – are the vast majority, facing down a regime that has to try to seize the powers of authoritarianism exactly because it lacks this popular support. Building and reinforcing opposition – active, engaged opposition – is important work.

With these gatherings, including the epic No Kings rallies, marches, and protests of October 18, we show up for and with each other, in solidarity with each other and with the people, rights, truths, science, institutions, and places under attack. We reinforce each other, remind each other that each of us is not alone, that we are strong, that we are committed. (And we amuse each other with witty signs; I'm often struck at a major demonstration that these scraps of cardboard add up in their hundreds and thousands to an irreverent, slangy, sometimes profane but cogent analysis of the situation.)

That moment when a cultural event suddenly became inflected with the imagery of a political protest – I think people were thrilled to feel that disruption, to see something speak to exactly the moment we're in. And then afterward, a handsome Latino man with a slight accent came up to me and said, "I need your poster." I hadn't intended to give it up, but I asked why, and he said that he is an immigration lawyer, and wanted to frame it in his office, where it would greet his clients. I wanted them to see it too – that is, he had me convinced that it would reach more impacted people, perhaps reinforce them the way the poster had my friend in the parking lot, that it would matter more in his office than my window, and so I gave it to him – on the condition that he offer a free consultation to the first immigrant I came across who needed it. I thought that would just be an ace up the sleeve, something to use who knows when.

And then that weekend I was talking to a friend of mine who's in the hospitality industry, who told me that one of her beloved workers, who had been with her for twenty years, who was dear to her and good at everything, was in ICE detention. So I reached out to my new lawyer friend sooner than expected, and connected them, and he prepared to help this captive of the Trump Administration. That part of the story is unfinished – but the way a piece of paper with a message caused so many ripple effects in the course of its journey across a city delighted me. I wonder what has become of the hundreds of others, what windows they adorn, what swaps have been made with them, what hearts they've encouraged. I saw three at the November 2 Day of the Dead procession in San Francisco's Mission District (pictured below).

All this reminds me that while people talk about all the forms of resistance we should engage in, most of these are very specific acts outside our everyday lives – joining groups like Indivisible, showing up at protests, writing or calling politicians, donating, voting. They matter. But a really significant part of the work is just speaking up, and not just in public – letting people know where you stand, talking about what matters, speaking with accuracy, clarity, and conviction about the situations we face, standing on principle, encouraging people to know that we have power and can use it, refusing to be swayed by those posturing defeatists who pretend that there's nothing we can do and the outcome has already been decided. And yeah, signs, buttons, t-shirts, and stickers can do some of this work too.

That's not a case for having arguments with people you disagree with (partly because the essence of arguments is that you can change the mind of the other person or prove them wrong, and that's something some people are good at – I'm not – but the really work is mostly to inform and reinforce those who are on our side, or to let those who are not see your conviction and maybe hear your facts and sit with that, not fight you over it). Because a lot of what matters is intangible: it's how informed and how engaged the public is, and both those things are fed by conversations, by the contagiousness of courage, by the facts that remind people of the reality of the situation, including the reality that sometimes we win when we show up. Public opinion, public resolve is made up of countless individual opinions shaped by countless individual influences. Be one of them.

We are supposed to believe that the troops sent to Coast Guard Island stood down because wealthy and powerful men talked to the president on the phone. But I think the immediate, well-organized, and fierce opposition may have played a role, and if it did of course they'll never acknowledge it. They never do, because convincing themselves and us that we have no such power is essential to their worldview – and their power. In the bigger picture, the solidarity we're seeing with immigrants is a beautiful thing, born of empathy and indignation – and a reminder of our power, because it is genuinely working, directly in some situations, and by informing politicians and the public that this will not go down without opposition, and reminding the people who are targeted that some of us care.

I did not know on January 20th how people would show up, and what they'd show up for, but of all the issues it could have been, immigration is in many ways the most powerful, the most profound, the most moving – solidarity across national and racial lines, a broad human rights campaign, and a recognition of the inherent rights and dignity of every refugee and immigrant above and beyond their crucial role in the economy that may make the USA a better, more united country in the long run.

p.s. You can download David's poster at: bit.ly/artnotoligarchy

Questions for subscribers: I try to send out a newsletter every week, and sometimes it's less than a week, sometimes more, depending on the news and my own schedule. Do you want it to run on a regular schedule?

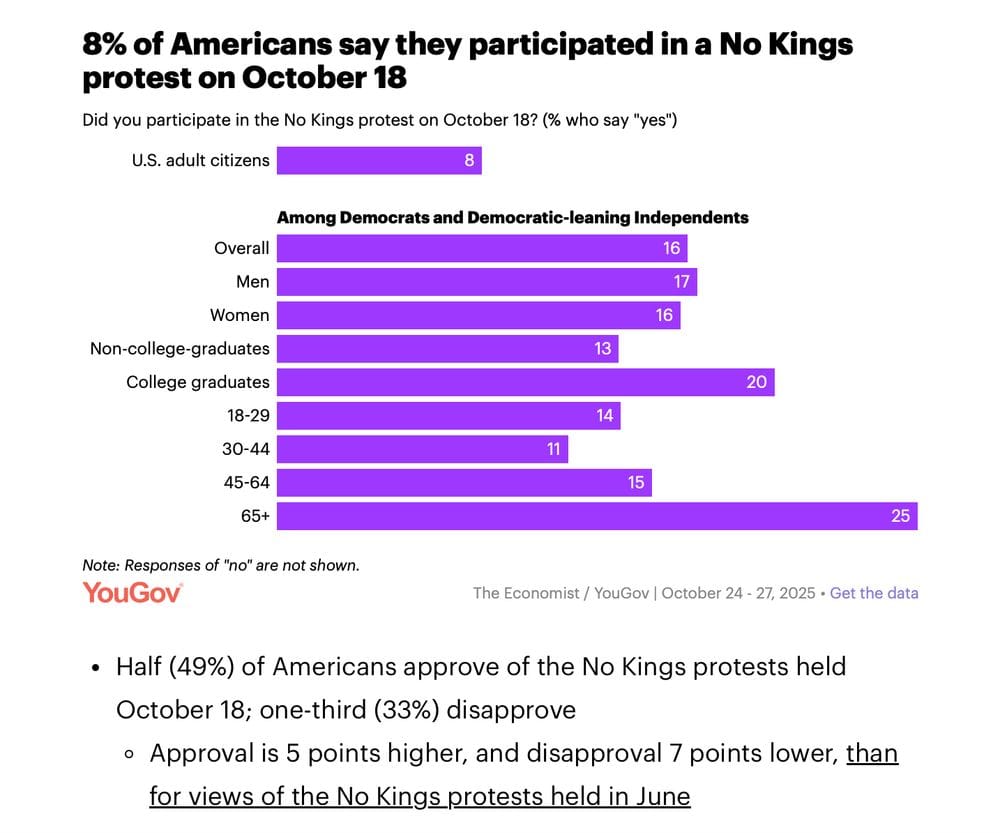

p.p.s. Speaking of the power of protest, the public-opinion research firm YouGov asked residents of the US a bunch of questions you can take a look at in the link below. One was about turnout for #NoKings on October 18, and while I'd really like to know exactly how the question was worded and understood, the answer to how many people participated suggests a stunning turnout. If eight percent of adults in this country did, that's about three times the seven million figure that's been settled upon. Whatever happened at the more than 2700 events across the nation, that so many want to say they participated shows the popularity of the event (and the Crowd Counting Consortium should eventually have some definitive data but their process is careful and far from fast).