Solidarity Stitches Us Together: Today, World AIDS Day, Is Also the 70th Anniversary of Rosa Parks's Historic Protest

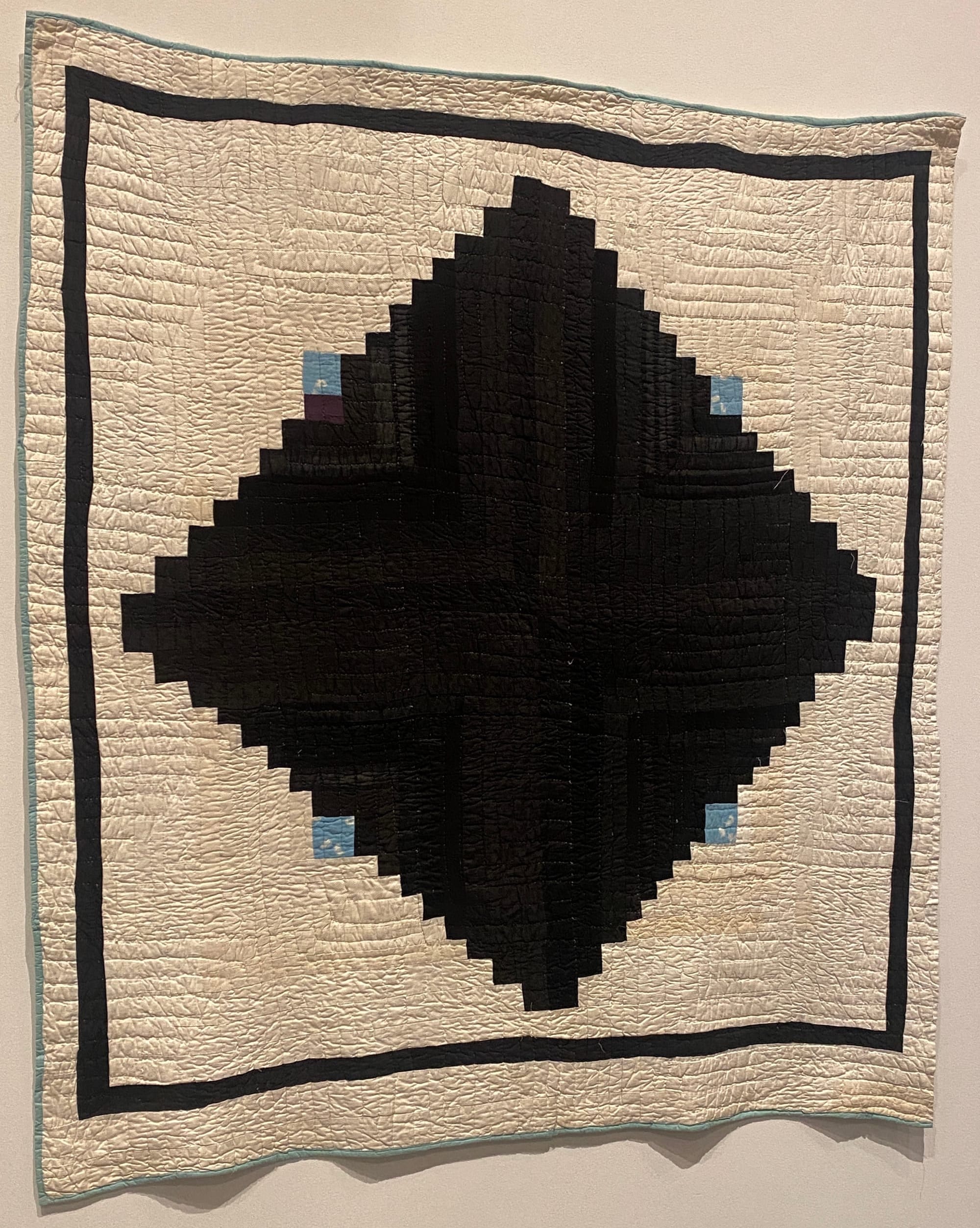

I saw two radically different versions of what a quilt could be yesterday and yet they spoke to the same issues. I caught the show Routed West: Twentieth-Century African American Quilts in California at the Berkeley Art Museum Sunday afternoon. I love quilts and while I could love them purely for aesthetic reasons, the fact that they're a traditional craft usually made by women, a technique of recycling scraps and worn-out clothes, and maybe a metaphor for putting the fragments together into a new whole makes them meaningful as well as beautiful.

They have often been the work of poor and rural women, providing warm covers for their beloveds to sleep under But they aren't just works of necessity or need; they are bold works of art, whether their creators follow established patterns or innovate wilder conjunctions – and Black seamstresses, including the famous artists of Gee's Bend in Alabama, have seemed freer and bolder in their quilt-making, going for what could maybe be described as a free-jazz approach to how fabric can come together, not sticking to the proprieties of traditional pattern. Patchwork quilts as distinct from whole-cloth quilts seem like a particularly American art form, and the United State is itself a patchwork of cultures, regional identities, ethnicities – this country's old motto e pluribus unum (out of many one) is a patchwork motto and one under attack as a hate-fueled administration tries to define down who has rights, who matters, who belongs – to tear up the great national patchwork and reject pieces of it no matter how long they've been here.

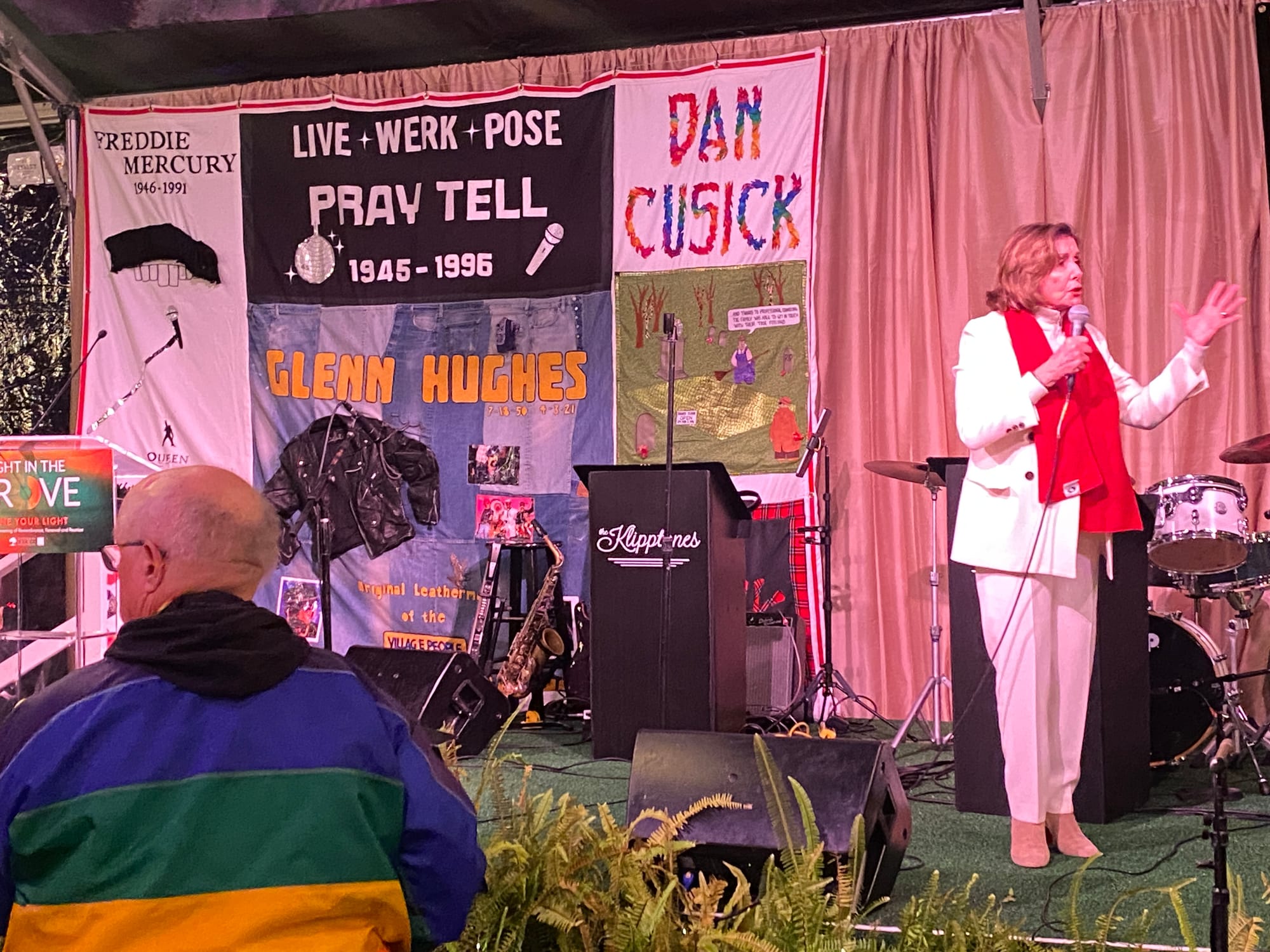

And then I went to the National AIDS Memorial gala in Golden Gate Park, where the memorial to that pandemic is a grove of redwood trees in which commemorative installations are scattered. At the gala, I spent time looking at the digital kiosk that lets users explore the AIDS quilt that is now part of the memorial and admired the actual panels used as backdrop to the event stage.

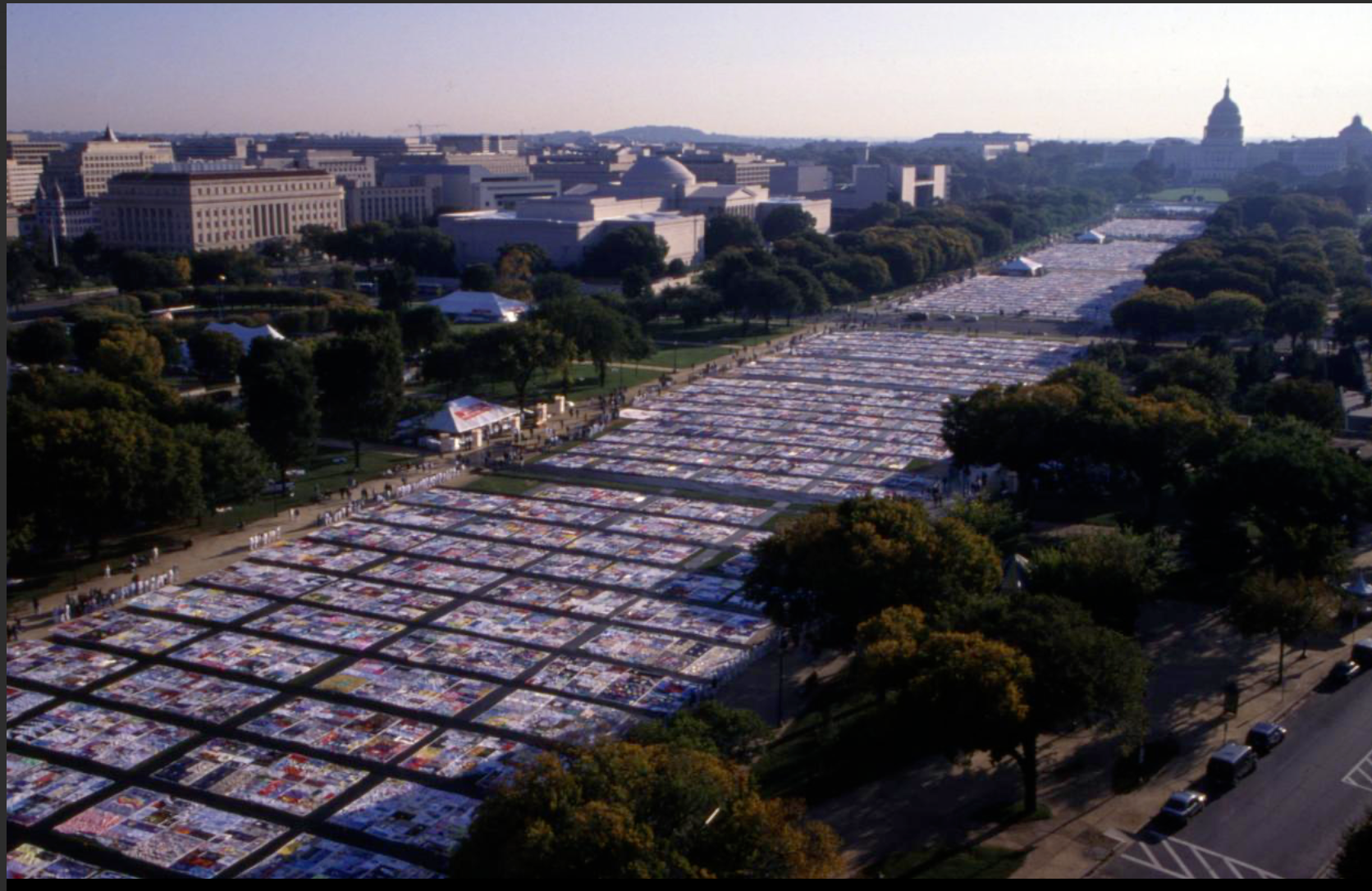

I was there as a guest of my friend Cleve Jones, who has been, of course, a legendary organizer in the San Francisco queer community since the late 1970s and is perhaps best known as the person who in 1985 dreamed up the AIDS quilt and launched it in 1987 as the Names Project, in which many thousands have participated. People were invited to craft three-foot-by-six-foot pieces commemorating someone who had died of AIDS, at a time when it was a raging pandemic for which there was little treatment and the gay community in particular had been devastated by the disease. They did. "Today, there are roughly 50,000 panels dedicated to more than 110,000 individuals in this epic 54-ton tapestry" says the project's website. That website has a searchable database where you can look for names; I looked in vain for a friend who died of the disease in 1993, scrolling through hundreds of Davids, after the hundreds of Dans. It's an open-ended project with panels being added all the time and ongoing maintenance on the existing ones (and I hope to craft one for my friend to add to it).

Cleve writes in his vivid, powerful memoir When We Rise, "Even the word had power for me. Quilts. It made me think of my grandmothers and great-grandmothers.... It spoke of cast-offs, discarded remnants, different colors and textures, sewn together to create something beautiful and useful and warm. Comforters. I imagined families sharing stories of their loved ones as they cut and sewed the fabric. It could be therapy, I hoped, for a community that was increasingly paralyzed by grief and rage and powerlessness."

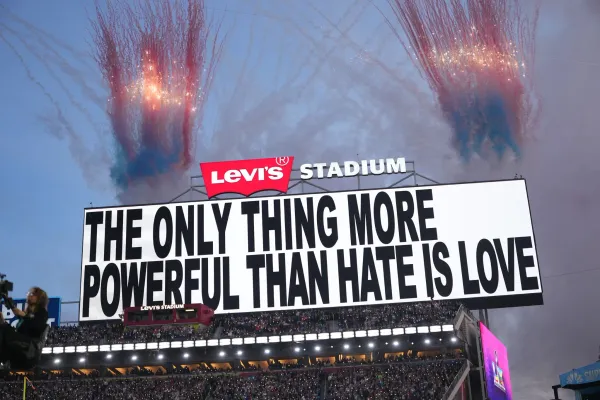

His vision became an extraordinary reality, a vast collective project that both made the sheer scale of the pandemic visible and testified that it was not abstract numbers, but individual lives, beloved sons and lovers and friends and brothers (and some sisters) who had died. Young people may not remember the ferocious brilliance of AIDS activism in the 1980s and 1990s, of ACT-UP and Queer Nation and all the rest, of their protests, die-ins, creativity, persistence, and leadership in pushing for AIDS research, access to treatment and education, in an era whose homophobic leaders undermined access and rights. I realized as I wandered among the people and displays at the gala that while Cleve has often expressed what sounds like despair he has never given up, not when his dear friend and mentor San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk was assassinated, not when the AIDS crisis hit San Francisco's queer community hard, not when Donald Trump came into power. When trouble and grief arrived, he organized. I'm proud to know him.

Today is World AIDS Day, and while the Trump Administration in its eternal spite and malice has decided not to observe it, the commemorative day is both global and something everyone can observe without the help of these butchers whose destruction of USAID has consigned countless souls in Africa to die of AIDS. As the Independent reported, "The UN’s Aids agency (UNAIDS) is forecasting millions more HIV infections globally by 2030 because of funding cuts, just at the moment new drugs should have been putting the end of the pandemic in reach. The report was published 10 months after Donald Trump cancelled three-quarters of the world’s funding for HIV at a stroke. In it, the agency has projected 4 million extra HIV infections by 2030, chiefly as a result of the collapse in prevention services."

But December 1 is important for another reason too. Seventy years ago today in Montgomery, Alabama, a Black civil rights activist and seamstress famously refused to yield her seat on the bus, which got her arrested, which got the town's Black community organizing, which got a young minister there named Martin Luther King involved in political activism in a whole new way, which begat the Civil Rights Movement, which didn't just change the United States but forged essential tools for rights and justice movements all over the world ever since. It began with Rosa Parks. Her activism did not begin, as we used to be taught with that event on the bus.

As more recent books about her recount, she had been working for more than a decade as an investigator for the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). Her dangerous work included investigating the rape of Black women by white men. She had a grandfather who introduced her to the work of Marcus Garvey and who refused to submit to the terrorism of the Ku Klux Klan; as a child she had stood beside him while he held a shotgun to defend rather than surrender should they come his way. She married a barber, Raymond Parks, who was also committed to the struggle for rights. There were already organizing communities in place on December 1, 1955, and she was not a tired lone figure but a catalyst for a movement whose groundwork had been laid. People around her sprung into action, recruited much of the Black community of Montgomery to join the bus boycott and organize alternative transit, spoke up, stood up, stood together, stitched themselves into powerful solidarity – and won the desegregation battle after more than a year of boycotts.

"When I went to Montgomery as a pastor," Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, "I had not the slightest idea that I would later become involved in a crisis in which nonviolent resistance would be applicable. I neither started the protest nor suggested it. I simply responded to the call of the people for a spokesman." Rosa Parks started it. It of course changed his life and then changed everything. When the queer activists demanded a better response to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and 1990s, the strategies and principles of the Civil Rights Movement underlaid their strategies and tactics. When activists today stand up for immigrants (and anyone and everyone ICE sweeps up regardless of their status) or for climate action or trans rights, we are heirs to the Civil Rights Movement.

It all began with Rosa Parks on that day exactly seventy years ago. Her bold act made first a city's Black population stitch itself together into solidarity in action, and then communities across the Jim-Crow south, and then changed the nation. It was as if she was the needle that first began stitching the fragments of resistance, hope, determination, vision together. Parks was a skilled seamstress who did that work for a living, but made quilts for love, even after she left Montgomery for Detroit and became a staffer for Congressman John Conyers. And she sewed squares for Cleve's AIDS quilt; the site that told me so states "Rosa Parks changed the pattern of history by sparking a powerful movement in the name of Civil Rights. It was this same drive to help her community that moved her, a talented seamstress by profession, to use her skills to memorialize and honor those who lived with HIV/AIDS."

The fabric of this country is forever being torn apart by hate and exclusion; it is forever being stitched into, as the site says, new patterns, new connections, new relationships. Solidarity is always about connection across difference, about the way you stand with someone you have something crucial in common with but who may be different in other ways. It is a quilter's art of bringing the fragments together into a whole. It is e pluribus unum.