Staying with the Trouble (Is Not Necessarily About Geography)

I've always been annoyed by those people who, when they didn't like the outcome of a presidential election, announced they were moving to Canada. Those declarations seemed to be about comfortable people prioritizing remaining comfortable and not wanting to stick around the discomfort of an administration they opposed – or rather didn't want to oppose, just avoid. They wanted to leave the country to leave the struggle. But there are a lot of ways and reasons to leave. And to stay in the struggle.

Historians of fascism and authoritarianism Marci Shore, Timothy Snyder (who is married to Shore), and Jason Stanley have left their Yale professorships for appointments at the University of Toronto. A huge amount of criticism has been hurled at them as a result, apparently on the assumption that anyone who goes to another country is running away and avoiding responsibility to face the crisis upon us here in the USA, which seems to imply that to stay in the country means to stay in the struggle. It doesn't.

It seems likely these three scholars will stay with their commitments to teach about, write about, and speak critically about authoritarianism, including the version trying to crush democracy in this country. Because something quite striking happened to them since 2016, especially to Snyder and Stanley: they went from being academics known to a few to highly visible figures making an impact on public life here. Meanwhile, quite a lot of people who remain in the United States, including some of the people taking these potshots, are doing, if you'll pardon my swerve into academic jargon, pretty much fuck-all to fight fascism. These critics seem to think simply being in the USA is enough or that sticking around until you're actively persecuted is a moral obligation (even though the record shows that in too many cases it was too late to leave by that time). Or that taking potshots at allies is activism.

Not everyone can leave on the terms that these academics did, but that's not a reason why no one should, anymore than the fact that not everyone can afford a home or a dentist means that no one should have one. Optional suffering is often confused with solidarity; it's not, and taking care of yourself so you can take care of the larger realms is foundational to being a sustained and sustainable activist. Too, people don't always leave just to be comfortable and avoid engagement (and the "not everyone can leave" statements often seems to overlook that quite a lot of immigrants currently in this country left their countries of origin on foot and embarked on terrifying odysseys, risking violence and death to arrive here with nothing, as undocumented immigrants and refugees; the declaration really means not everyone can leave while preserving comforts and status).

If you're a writer and researcher, you can, to use Donna Haraway's resonant phrase, stay with the trouble in many ways, and the power of your voice is not limited to your locale. From Eduardo Galeano to Edward Said, writers have done important work in exile. And we are already in a time when people are getting harassed coming back into the country, having their mobile phones and computers scrutinized upon their return, being challenged because they've lost the ability to travel freely because they've dissented from the Trump Administration or belong to one of the groups they're targeting. Milwaukee County Circuit Judge Hannah Dugan has been arrested and charged on highly questionable grounds. Even US citizens have been seized and sent to ICE gulags, along with immigrant students who spoke up about Gaza, as ICE becomes a kind of Gestapo. Newsweek started a recent story this way: "House Republicans have voted down an effort to block immigration enforcers from using federal resources to detain or deport U.S. citizens."

Some leave authoritarian regimes because of persecution. But some leave to fight from out of reach of the regime, and examples abound including from occupied France during the Second World War and Latin American countries ruled by dictators in the 1970s and 1980s. These days I'm hearing from lots of people who have obtained or are trying to obtain citizenship in other countries – usually someplace their parents, grandparents, or great-grandparents came from. Those ancestors were sometimes fleeing persecution or genocide, as did my paternal grandparents (the pogroms were already terrible when they left the Pale of Settlement in their teens, and all the relatives who stayed behind were murdered by the Nazis as far as I know). Most of them are not planning on leaving unless they think they must for their own or their children's safety, though I do know people who have relocated within the US to protect their trans kids.

You can leave the country and stay with the struggle or stay in the country and not participate in the struggle, and to be blunt, the majority of people in the US are not participating. Turnout for the Hands Off protests on April 5th were the biggest since Trump came back to the White House, and though it might have been more than two million, that's well below 1% of the population.

Snyder in particular is notable for having stood up immediately after Trump was elected in 2016 to speak against the regime with the warnings he drew from his researches on Eastern Europe in the Nazi era with his immensely influential Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century. At that time, I was concerned that people would be too cowed to stand up, that there would be very little resistance, and that only a few would resist and be easy to pick off. This was two months before the January 21, 2017, Women's March and the following weekend when so many of us went to the airports to protest the Muslim ban and try to help people flying into this country who might be impacted, which was when I felt assured that people would show up. But Snyder made a huge impact a week or two after the election and has stuck with it since. (It's worth noting that his Twenty Lessons drew from his years of paying attention to other times and places, of being what might look like disengaged with the here and now, which turned out to be how he gathered useful perspective for the looming crisis of Trumpism.)

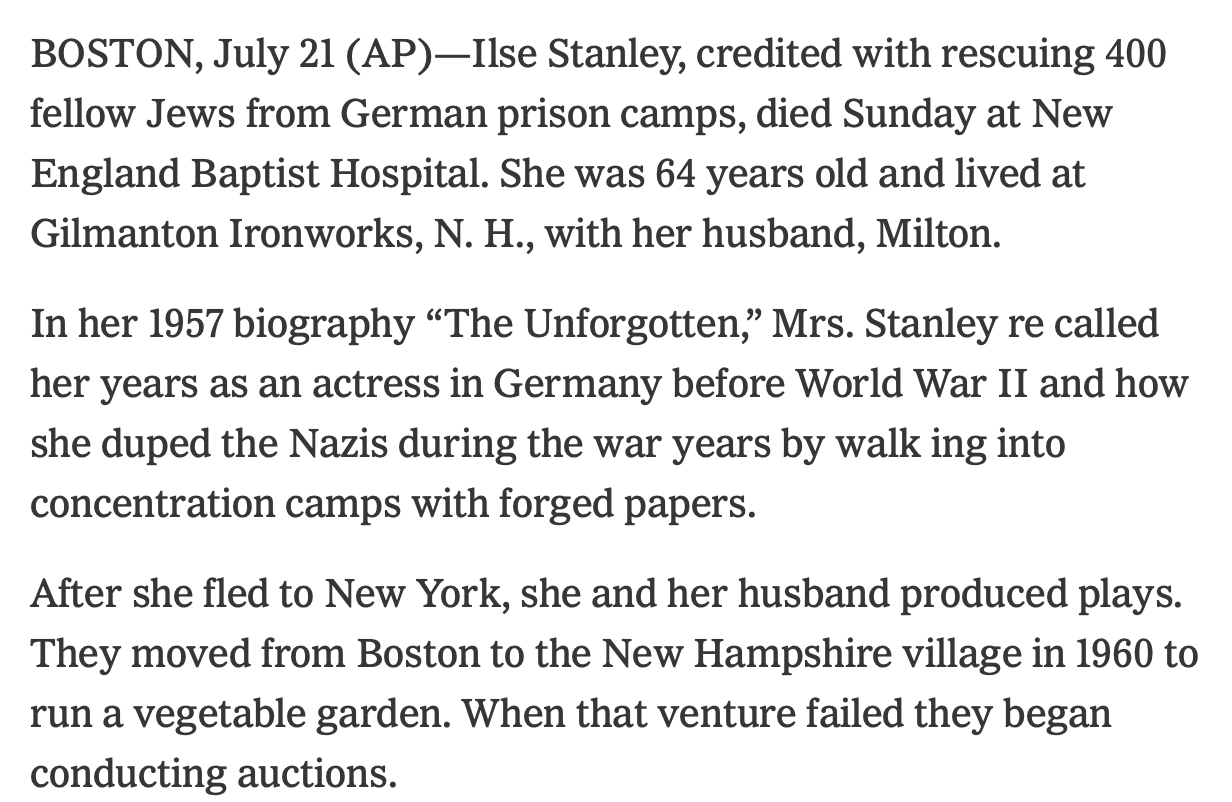

This prompts another perpetual question I have: if someone is doing good things, do they have to do them forever, or do they get to stop doing them at some point and still be appreciated as a person who did good things, rather than lambasted for the non-eternal nature of their contribution? Sometimes people burn out or get sick or just need to retire or do something else. Jason Stanley's legendary grandmother rescued more than 400 Jews from the Nazis, with brilliance and daring, before she left Europe for the USA (and had she stayed it seems unlikely she and her son would have survived).

The New York Times has pumped up the debate, with a short text and video that seem to have inflamed a lot of people's opinions. (I looked at the comments, I regret to say, which include "The point that is not made is that if every person who cares about democracy leaves the US, then there is no possibility of fighting for democracy, the constitution, the basic freedoms that most of us like, expect and take for granted," as if three people leaving means everyone will.) But it's not a video in which the three scholars talk about themselves. It's a video in which they talk about the analogies to previous authoritarian regimes they study, offer warnings, give examples about the trouble underway. In other words, they're still doing their work in the US.

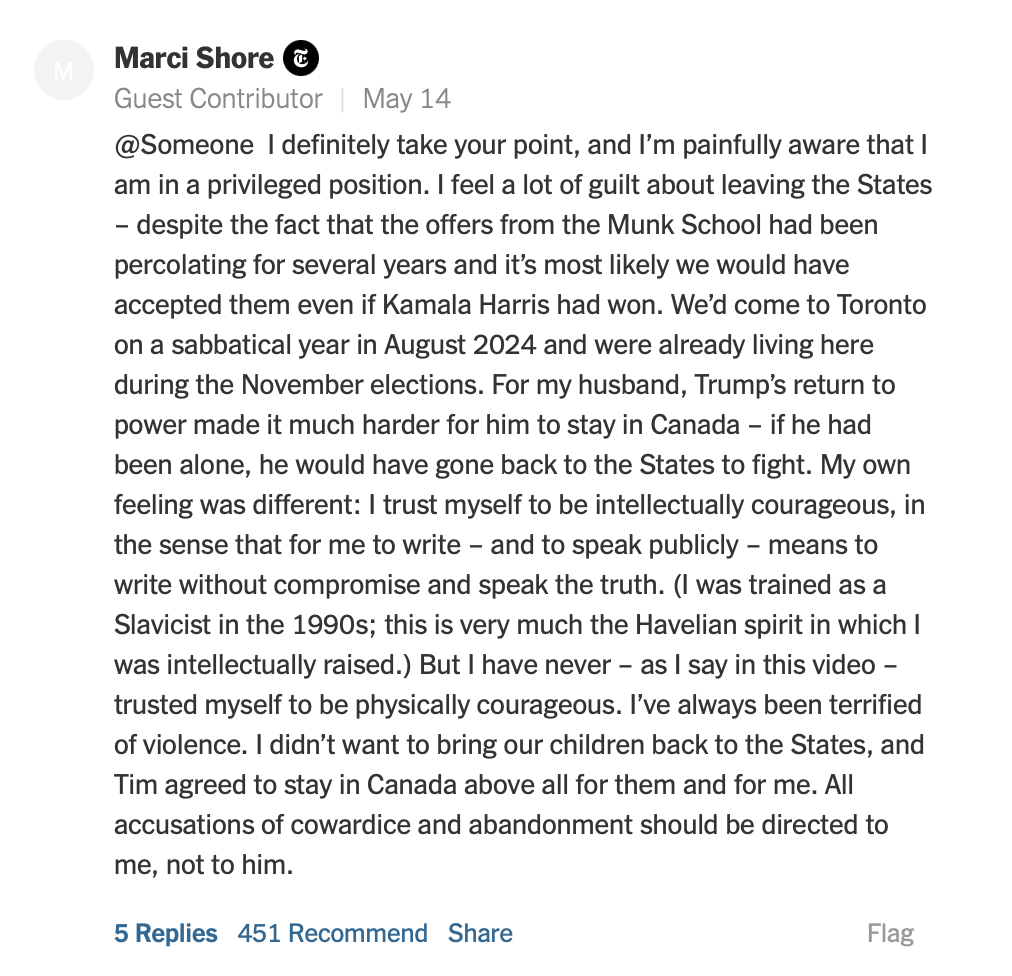

The New York Times's accompanying text includes this sentence about Snyder: "Primarily, he’s leaving to support his wife, Professor Shore, and their children, and to teach at a large public university in Toronto, a place he says can host conversations about freedom." It links to his own essay about his departure published in Yale Daily News, but doesn't include the crucial information that the University of Toronto had been making offers for years, and Snyder and Shore decided to leave well before the 2024 presidential election. Shore read the comments, many of which attack her savagely, and wrote the following reply:

But even if she's terrified of violence, she's not necessarily taking the safe route. She wrote recently of visiting Kiev, while the Ukrainian capital was under bombardment by Russia, and of hearing air raid sirens and seeing underground lecture rooms at the university she was visiting. She seems to avoid saying she was in an art gallery when this happened, but it sounds like a firsthand account: "When an air raid siren went off, the exhibit guide encouraged the visitors to relocate to the bomb shelter: "There is a concession stand and bookstore on the basement floor. Please go down and have a cup of coffee.'" Being in Kiev voluntarily right now: that's physical courage.

Snyder, in that Yale Daily News piece cited in the New York Times, sounds defensive or at least aware of the attacks on him. He lists the work he's done since moving last summer, including lecturing around the US, and supporting Ukrainians in very direct ways, including visiting the Ukrainian front lines (which seems pretty dangerous), helping to open a school there, and raising money for armored evacuation vehicles. But then he writes, "Personally, most everything I have had to say about the United States comes from looking at it askance, from the past of other countries, or from perspectives that I gained by living abroad. I did not move because of threats, denunciations, attempts at stochastic violence from low people in high places, sanctions by Russians, warnings from friends at home and abroad, etc. But what if I had? More to the point, what if people who are far more vulnerable than me, and they are legion, decide to leave? Some of them already have, and more of them will. We need to support such people and learn from them. There are many problems on the American Left, and a signal one is the tendency to turn our energy against ourselves." (Incidentally, he has an article about the Trump regime out on his newsletter today, calling Ed Martin the "weaponization czar" and noting his white supremacy and Putin-regime associations.)

Jason Stanley made a more recent and as he says, more impulsive decision to go, saying to National Public Radio, "I have Black Jewish children and the attacks on DEI are attacks on Black people. They're attacking Black history. They're targeting Black people in positions of power. And they're creating mass popular anger against Jewish people by taking Jewish people, by setting us up and saying we're the excuse for taking down democracy. Personally, I'm not going to risk my kid's safety for a political point." Vanity Fair's piece on Stanley has the accusatory title, "The Fascism Expert at Yale Who’s Fleeing America," and NPR likewise titled their article, "Why this Yale professor is fleeing America." The word fleeing in these stories is a loaded term widely read as an accusation and an attribution of motive.

I like public universities, and I'm happy to see prominent scholars go to places more accessible to the less elite (tuition at Yale is $67,250; at University of Toronto it's less than a tenth that for Canadians). They can do their work against authoritarianism and for democracy from their current location, less than a hundred miles from the US border just as well or maybe better. Given the way that some Ivy League universities have caved to the Trump Administration this year and that many of them did the same last year when Republicans in Congress conducted interrogations of their policies around Gaza protests, it seems reasonable to feel uncertain about those institutions' commitment to freedom of speech, thought, and association going forward.

And as highly visible scholars, outspoken critics of the administration, and faculty at universities already under attack (and in both Stanley and Snyder's case, critics of Israel), they have reason to fear persecution. "The U.S. Department of Education this week warned Yale University of 'potential enforcement actions' related to an investigation into alleged antisemitism as President Donald Trump has promised further crackdown on student protests," said a March report. As prominent critics of Trump, they may be facing threats from MAGA sources or pressures from administrations we don't know anything about, and being forced to focus on your own safety can take away the ability to serve the bigger cause. (Making threats public is often just an invitation to copycats.)

I'm big on the benefit of the doubt when doubt is possible, or at least on innocence until proven guilty, and I'm even more committed to the idea you're not entitled to an opinion until you're equipped with the relevant facts (and I've seen people leaping to convenient conclusions and rendering verdicts while also demonstrating they don't knowing what they're talking about, when it comes to this case and so much else, since social media made people feel obliged or entitled to weigh in on everything). Knowing that you don't know is the beginning of wisdom. And sometimes a manifestation of generosity. But in this case we do know the three people under attack are deeply engaged with the current domestic crisis.

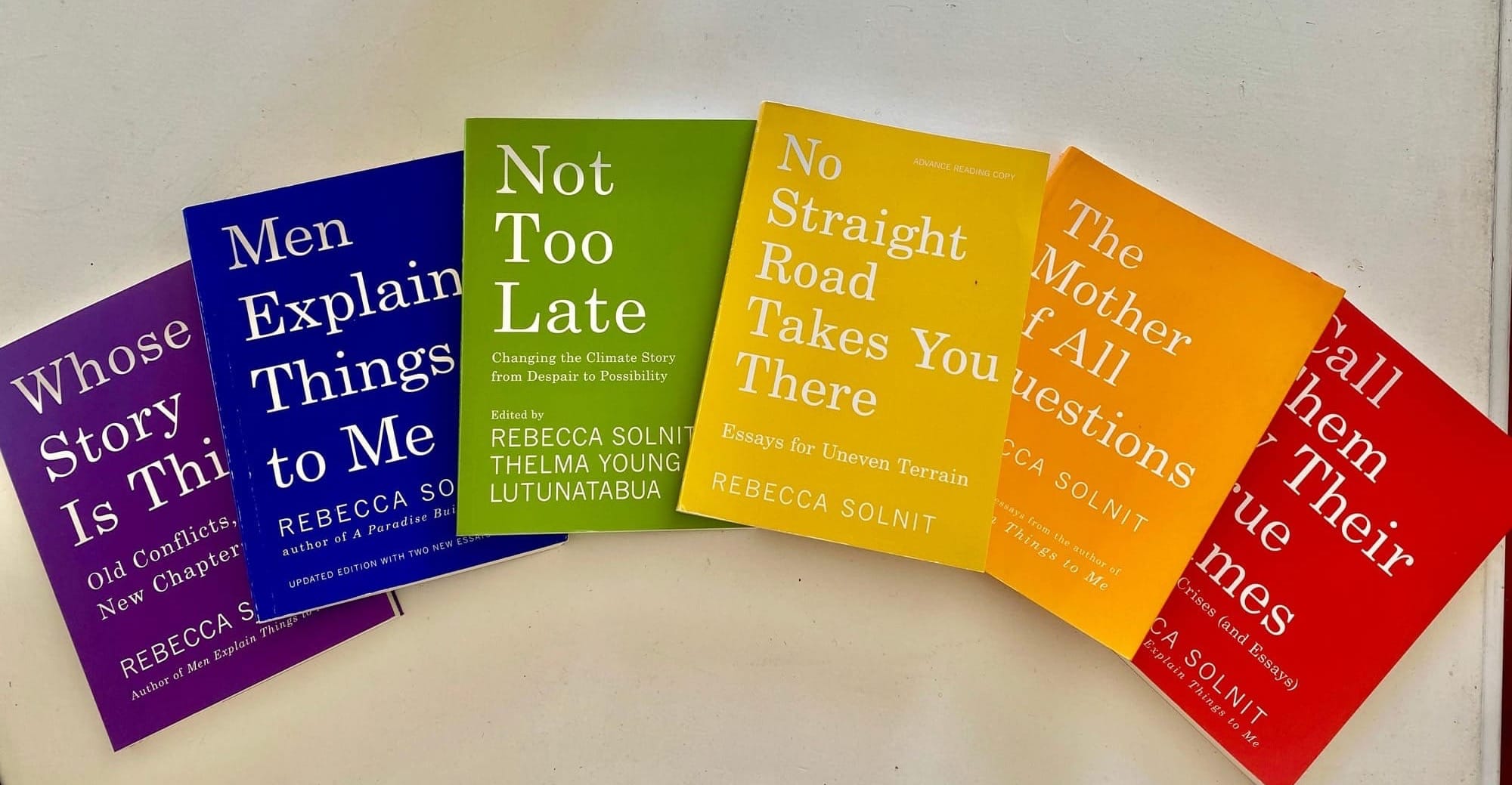

p.s. Some news from me: I started my book tour last week, and had wonderful times in Chicago (in conversation with Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, whose newsletter also hosted on Ghost I strongly recommend), in Seattle, and in Portland with that mermaid of prose Lidia Yuknavitch, and I'm leaving for Europe Wednesday, which may limit how much I can do here. But I'm also hoping to write about some of what I'm seeing and hearing while I'm there and very excited to see pedestrianized Paris while at Shakespeare and Company there.

Oh yeah, and the book is this yellow one that completes the rainbow that began in 2014 with Men Explain Things to Me, and my wonderful publishers at Haymarket got on board with this color scheme, which I hope bookstores will deploy on their shelves. That it's the same color scheme as the rainbow Pride flag Gilbert Baker designed at Harvey Milk's behest in 1978--or to get technical, the later state of that flag--delights me and was very intentional.