Stick With the Facts & Don't Be Like Them: Some Notes on a Recent Spate of Misreadings

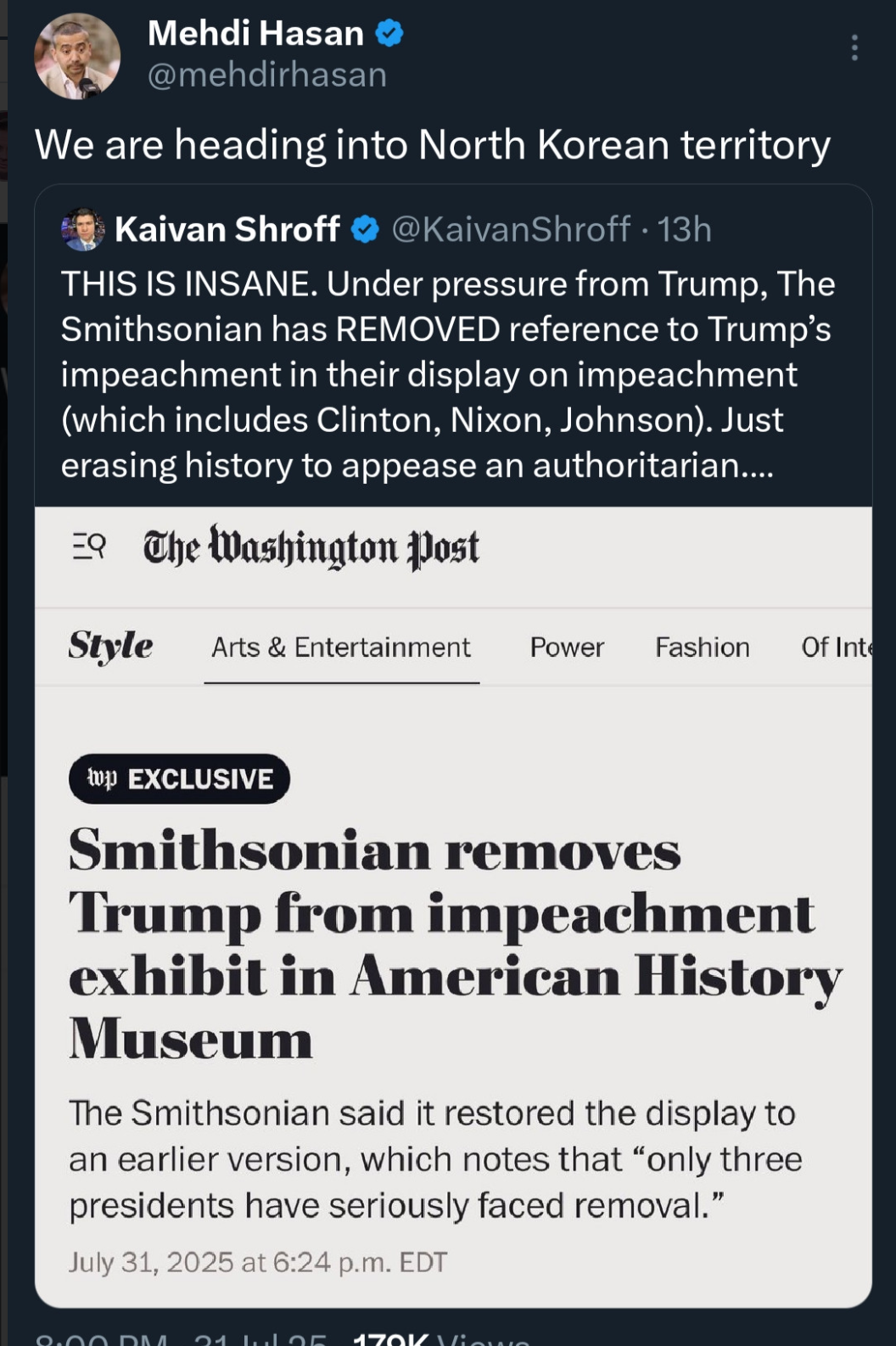

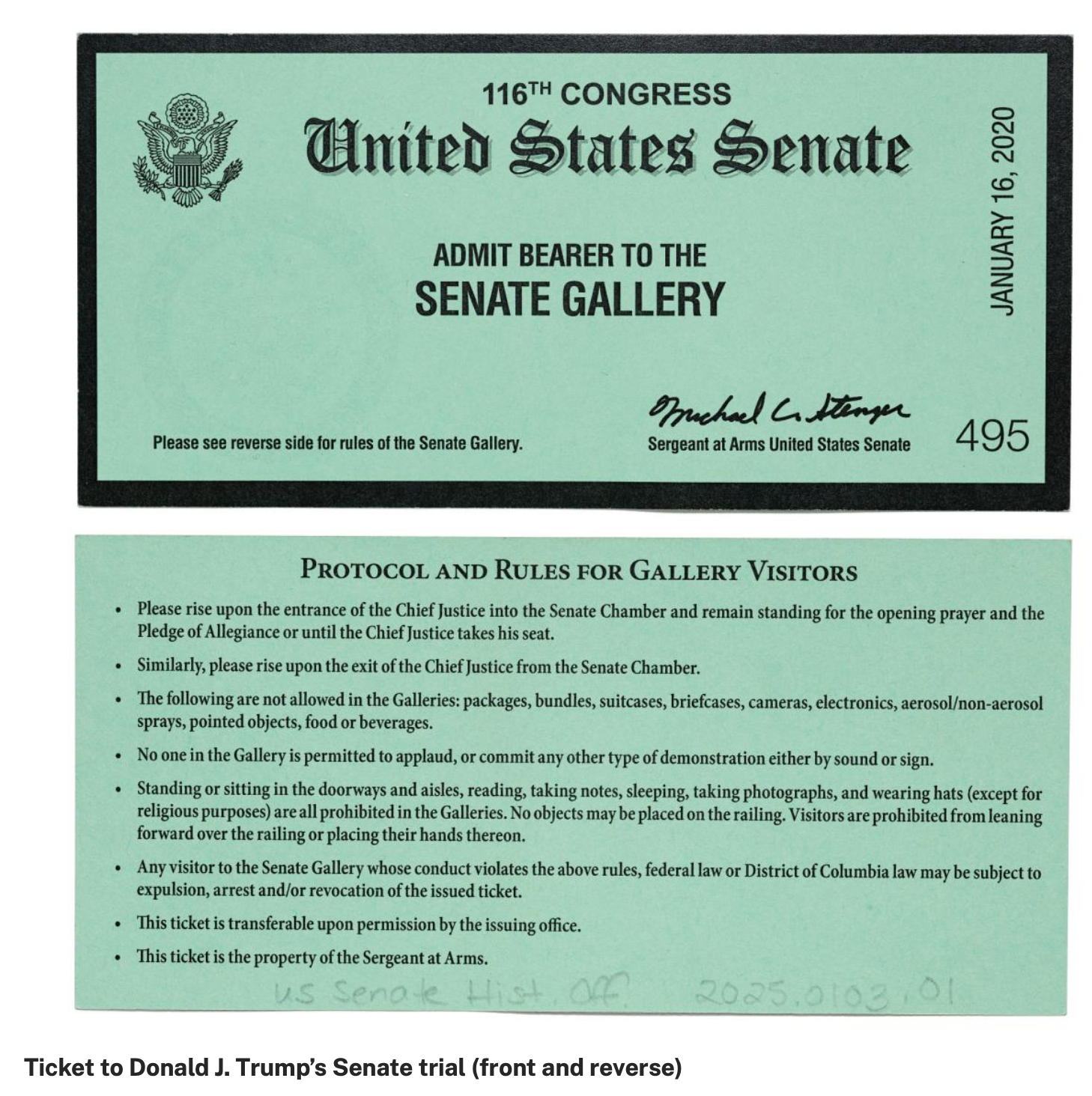

On July 31, the Washington Post ran a story noting that the National Museum of American History, a branch of the Smithsonian, took down a portion of an exhibit about presidential impeachment concerning Trump's two impeachments. The piece quoted an unnamed source: "A person familiar with the exhibit plans, who was not authorized to discuss them publicly, said the change came about as part of a content review that the Smithsonian agreed to undertake following pressure from the White House to remove an art museum director."

What seemed to be established fact is that that portion of the exhibit had come down. Was it under pressure from the Trump administration? Would it remain down indefinitely? Was the museum censoring history out of cowardice or acquiescence? People leaped to that last conclusion, by over-interpreting the statement by the anonymous source, who only said that it came about as part of a content review. Correlation is not causation, or, as one excellent unpacking of that catchphrase puts it, "If we collect data for monthly ice cream sales and monthly shark attacks around the United States each year, we would find that the two variables are highly correlated." But, it goes on to note, though both go up in the summer, ice cream consumption does not, in fact, cause shark attacks.

The reasons for taking down the exhibit were unclear. Nevertheless there was shrieking.

Two days later there was a follow-up in the Post, quoting the museum: “We were not asked by any Administration or other government official to remove content from the exhibit. The section in question, Impeachment, will be updated in the coming weeks to reflect all impeachment proceedings in our nation’s history.”

But now that people had convinced themselves (and lots of others; there was quite a ruckus on social media) that the museum had yielded to pressure from the administration in taking down the temporary part of the exhibit, they followed up on that by convincing themselves it had subsequently yielded to pressure from the public in putting up a new part of the exhibit, aka was a cowardly manipulable institution that had swayed one way and then another.

But nothing in the reporting provided grounds to reach that conclusion. The second conclusion was built on the first, the first was built on innuendo and over-interpretation. I don't know if what the museum said was true, but I currently have no reason to believe it's not true. I don't know is an important part of truthfulness and accuracy. ARTnews reported on August 11th that the new signage about Trump's impeachments had been installed in the display. The museum's website has an online exhibit about all US presidential impeachments.

It's fun and popular to rail about untruth and spin doctors and conspiracy theories in right-wing media, cults, propaganda, politicians' lies, and so forth. But quite a lot of people who consider themselves reasonable, well-educated, progressive and so forth are also liable to reach conclusions without a basis, sometimes with the help of mainstream media. Usually these are conclusions that bolster their worldview. Our worldview, to be fair.

They often seem either not to notice that there's no foundation for their conclusion or not to understand what constitutes a reasonably reliable source or verified fact. At worse they don't seem to know the difference between knowledge and speculation. Usually that speculation fulfills a desire to find coherence in the world or to validate a worldview, achieved by speeding past the warning signs flashing "unreliable source," "we don't actually know," "the future has not yet been decided," "evidence not in," and so forth.

Sometimes it's harmless. For me it was once really fun when a bunch of people did it about something I wrote. In 2012, Beyonce posted on her blog--or maybe someone who worked for her posted it--a passage from my 2005 book A Field Guide to Getting Lost, about the color blue. Print and social media quickly concluded that this was why she had named her daughter, born several months earlier, Blue Ivy Carter, and the story pops up periodically, linking my name to the goddess, and that part is really fun. But the post did not suggest, let alone state, that this was why the child was named Blue.

It was another conclusion without a basis. (Fun bonus misconception: my essayistic nonfiction book was described as poetry and fiction; sad bonus fact: it did not lead to a sales boom.) So far as I can tell, people were eager to scry meanings in it the way ancient oracles saw meanings in the entrails of sacrificed animals, and so they did. At least people eager to over-interpret Beyonce posts about baby names are not maligning anyone or anything or making our political situation worse or our public more vulnerable.

Nevertheless this blurriness is dangerous. There's a famous, oft-quoted passage in Hannah Arendt's The Origins of Totalitarianism: “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.” It is usually used against some version of people we see as those other people over there not at all like us – QAnon and anti-vax conspiracy theorists, people who believe what Trump says. But it is all too useful a description of quite a lot of us.

I was fortunate to have a good education in careful reading: I was an English major, then had a fact-checking internship between college and entering the Graduate School of Journalism at UC Berkeley, and while in grad school being trained not only in gathering facts but in the ethical responsibilities of the storyteller, I had a work-study job as a research assistant at SFMOMA that gave me another kind of training in finding things out and getting them right; then I worked as an editor and copyeditor for almost four years, while writing art criticism whose interpretations arose from looking carefully and understanding the context and references.

That training was good for reading texts critically, and everything made out of words counts as a text here: slogans, newspaper stories, political speeches, public signage and place names. For finding the assumptions behind them, for perceiving the way words work to make us think and feel things and how that can be done honestly or dishonestly. For asking good questions, including what has been left out and what's the agenda of the speaker. To see the echoes, the layers, the patterns, the excluded and alluded-to parts of a text, its relationships to previous texts, to be prepared to answer good questions about narrators, reliable and otherwise, underlying values and assumptions. It's not the only way to get there; the legal profession, humanities educations, detective and intelligence work are among the ways people get trained in being careful and attentive to facts and language.

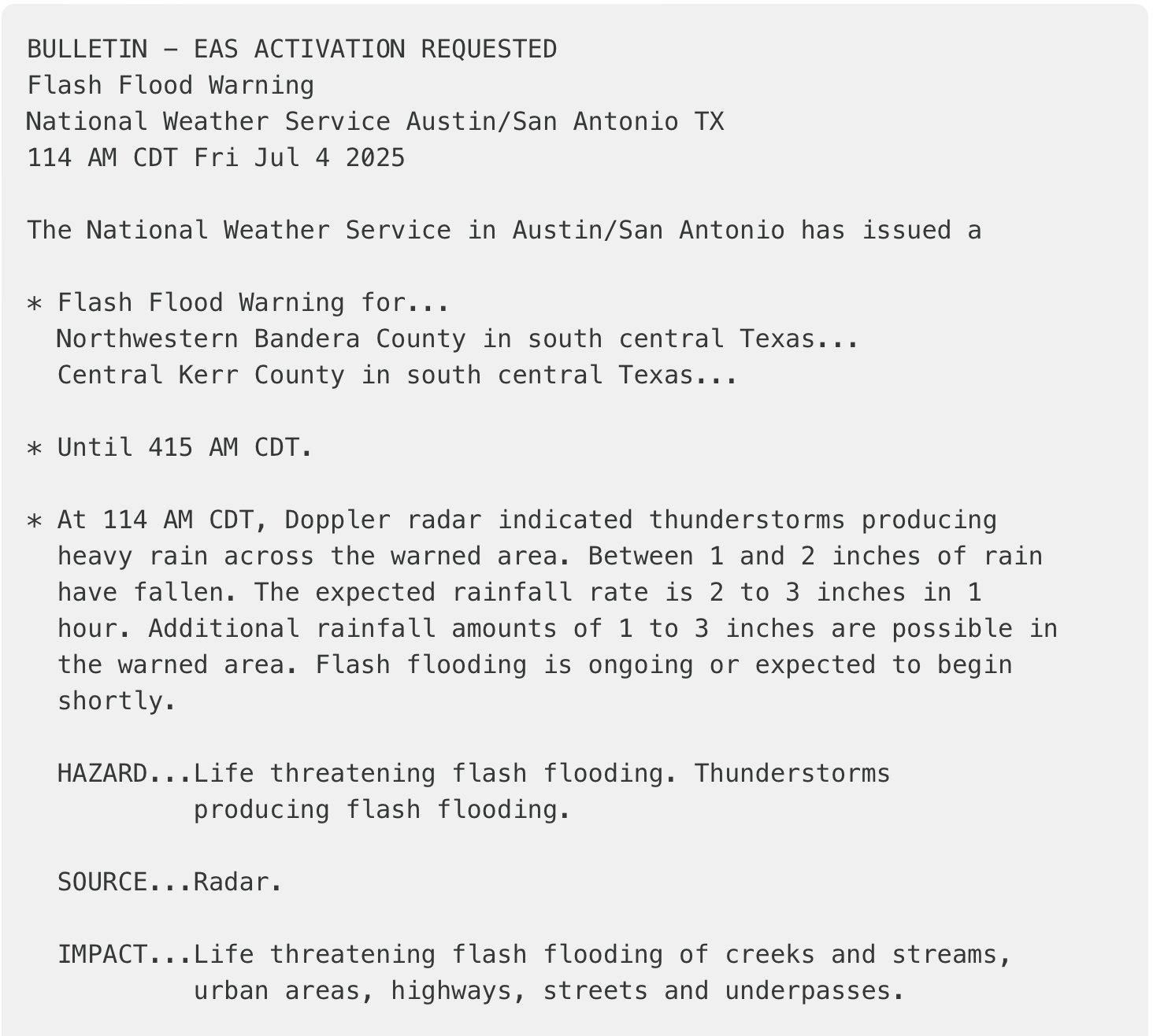

Shortly after the terrible floods in Texas, the New York Times published a story that led a lot of people (including some prominent ones who shared it widely) into concluding, erroneously, that because of cuts the National Weather Service had failed to give adequate warnings. The New York Times is unusually prone to publishing what appear to be news stories that are packed with manipulative language and skewed facts, and this was a prime example.

I wrote in the Guardian shortly afterwards: There were two opposing reasons to blame this vital government service. For local and state authorities, blaming a branch of the federal government was a way of avoiding culpability themselves. And for a whole lot of people who deplore the Trump/DOGE cuts to federal services, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Weather Service, the idea that the NWS failed served to underscore how destructive those cuts are.

Many of them found confirmation in a New York Times story that ran with the sub-headline: “Some experts say staff shortages might have complicated forecasters’ ability to coordinate responses with local emergency management officials.” Might have is not “did”. Complicated is not “failed”. It’s a speculative piece easily mistaken for a report, and its opening sentence is: “Crucial positions at the local offices of the National Weather Service were unfilled as severe rainfall inundated parts of Central Texas on Friday morning, prompting some experts to question whether staffing shortages made it harder for the forecasting agency to coordinate with local emergency managers as floodwaters rose.”

A casual reader could come away thinking that staffing shortages had had consequences. But if you give the airily innuendo-packed sentence more attention, you might want to ask who exactly the anonymous experts were and whether there’s an answer to their questions. Did it actually make it harder, and did they actually manage to do this thing even though it was harder, or not? Did they coordinate with local emergency managers?

The piece continues, “The staffing shortages suggested a separate problem, those former officials said,” and “suggested” sounds like we’re getting an interpretation of what these anonymous sources think might have happened or been likely to happen, rather than what actually did. Suggestions are not facts. Likelihoods are not actualities. In other words, there’s no answer to the suggestions and questions and intimations. Nevertheless, a lot of readers gathered the impression that this was not speculation aired by unnamed experts but confirmation that the NWS had failed.

Language that wants to get us on board by means of deception, omission, insinuation is always putting out bait for us. Learning not to take the bait is in part about learning how to use the language and recognize how it's being used. Too much of what's served up as news builds a big ruckus out of something minor and dismisses something major. Or it accepts and recycles lies.

Again, it's not just them; it's us. Here's another example. Earlier this week, constitutional law professor and expert on marriage equality Tobias Barrington Wolff noted: "The media are so eager to queue up an overruling of the Supreme Court’s 2015 ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges and the constitutional right of same-sex couples to marry that they are taking every news item on the subject no matter how minor and turning it into a blockbuster.... Kim Davis is the tawdry spectacle the media want right now but her case is not the one the Court will take to reverse itself on marriage equality." Davis is the wacko former county clerk from Kentucky who got into trouble after marriage equality was affirmed a decade ago for refusing to issue licenses. She doesn't deserve the attention and she doesn't have the power.

Being careful about the use of language is useful for surviving authoritarianism because authoritarianism seeks to control fact, truth, history, reality itself through misleading, false, inflammatory, and distorted language, as well as suppressed information, and to make it the norm. Right now, the kind of resistance that means, say, blocking an ICE van or joining a march matters. But resistance to the corruption of language and the blurring of the boundaries between true and false also matters a lot in this crisis.

In February of 2017, I saw where we were headed and posted this: "Love of truth is an important love. Precision is as beautiful in language as it is in dance. Getting our facts right is an important form of respect, even love, for what matters in our public conversations and political, cultural, intellectual (and personal) lives. As we endeavor to survive a regime based on barrages of lies, truth should be even dearer to us; facts are part of our arsenal and what we are defending; accuracy and honesty and carefulness are essential ways of being the opposition." I still love accuracy and precision, and I still think they are ideals and tools we need to hold close.