The Art of Arrival

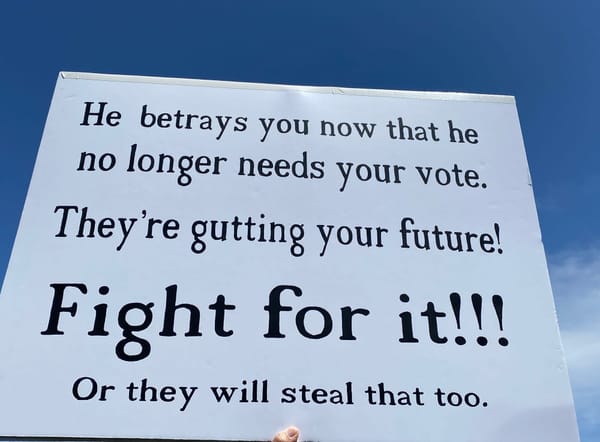

I published this in Orion Magazine in 2014, about the environmental activist Jo Anne Garrett of Baker, NV, who would've turned 100 on April 30th. I wanted to pay tribute to her by republishing this (slightly shortened) essay about her. The Las Vegas Water Grab mentioned in it--the attempt by that city to siphon off the water vital to life in eastern Nevada to feed the city--was definitively defeated in 2020, seven years after Jo Anne passed away, 31 years after she and other rural Great Basin residents banded together to defeat it and stuck to their cause through setbacks and switchbacks to ultimately win. Though this essay has politics in it and is about a very politically engaged elder, it reminds me of who I want to be as a writer when the crises aren't so urgent as they are now. I'll be back to writing about the 2025 coup in the next piece (but I founded this newsletter hoping to write more lyrical, literary, and personal things here, as well as cover politics--more meditations, less emergency).

The word “journey” used to mean a single day’s travels, and the French word for day, jour, is packed neatly inside it, like a single pair of shoes in a very small case. Maybe all journeys should be imagined as a single day, short as a trip to the corner or long as a life in its ninth decade. This way of thinking about it is affirmed by the t-shirts made for African-American funerals in New Orleans and other places that describe the birth date and death date of the person being commemorated as sunrise and sunset. One day.

I caught up with Jo Anne Garrett late in her journey, when she had come to rest and I was learning to roam. In those days, I would devour the six hundred miles between my home and Jo Anne’s in a day and try to arrive before sunset, when we would sit up on the deck that reached east from the second floor of her home and watch the shadows of the sun behind the mountains stretch far across the desert floor and across the invisible line between Nevada and Utah. Dozens of miles beyond, at the other end of Snake Valley, Notch Peak sat on the far horizon, sharply visible across all that dry air.

She had lived there in a house she had built herself with the beloved for whom she had left her first husband in the 1960s, and she lived there long after he had died, serene, with the air of someone who has truly arrived, not restless for other places, for life to change, for company or bustle or entertainment. She lived in that magnificent house with its tall wall of windows facing the mountains to the west and its deck looking on that dry ocean to the east like a priestess in her temple. She lived there to carry out the small rituals of her day, bear witness to the light that changes continuously, day by day and over the course of the year, and love the place and a number of people.

It was the last act of a long life in which she had been a Montana farmgirl who had saved up and gone to college, had married young and had four children, the proper trajectory for a woman in those postwar years, had left that husband and struggled to maintain her relationship to those children, had married a younger man who brought her to a place his mother had ties to, Baker, Nevada, a small hamlet far from everything else. If everything else is supposed to mean cities and commerce and crowds. It was close to the sky and to Wheeler Peak, at 13,065 feet the highest mountain wholly inside the most mountainous state in the union. You couldn’t see that peak out her windows; as is often the case, it was hidden behind peaks that were nearly as tall. People can be like that too, where the person who changes the world or makes the system work is hidden behind others.

She had done that rare thing in an American life in our time: she had gotten to where she was going, though her life was still full of journeys, mostly full of drives to meetings about environmental politics. Even the nearest grocery store was in Ely, Nevada, seventy miles away.

[ 2. ]

You travel to get away from something, and though people caution that you can’t run away, you can, and sometimes you should. After all, this is a country full of people who were running away—my father’s parents from the pogroms and massacres, my mother’s grandparents from the famines and anti-Catholic laws, rural kids from the brutalities of agriculture and the limits of small towns, city kids from the slums or the harshness, suburban refugees like me escaping anomie and homogeneity.

Nowadays we are encouraged to think that travel is for variety and discovery, but travel has its own rhythm and routines, and maybe the best journeys are the ones that are worth repeating and are repeated. That’s what I had for the years when I plunged into the West every summer and stopped at Jo Anne’s. This is how home becomes bigger, the opposite of leaving home. And home has to mean something more than a house; it has to mean a place, so that going out the door can be going home as much as going in.

But there are many kinds of travel, many reasons to move. Sometimes you travel so that the process of becoming that is your inner life has an external correlative in your movement across space. You may not know how to save your soul, but you know how to put one foot in front of another. You may not know the way to stop being so furious you can hardly sleep, but you can buy a road map of the American West. And then you can put the need on like a knapsack and wear it along your journey, wear it out, shed it, find that it belongs to someone you no longer are. This is pilgrimage, which is not as pretty as it sounds. It’s not running away, though: it’s running toward.

[ 3. ]

Jo Anne was for those seventeen years of our friendship the gravitational center around which I orbited the West, she and that house. The first time I visited her, she took me up to the heights where the bristlecones grew, and after that she stayed home and left me to explore the vicinity on my own. I went out; I came back. I went away to the West Coast, and came back again on my way to New Mexico or my way back from it. When I first started coming she was robust and the grocery store in Ely had almost nothing fresh; a decade in, she was a little frailer and there was a vast new grocery store with a long aisle of gleaming green things. But the house never changed.

A low polished teakettle always rested on the old gas stove. A bright yellow enamel pitcher with wickerwork woven around its handle sat on the counter. Wooden plates and earthenware ones sat on open shelves. A tiny green lawn like a prayer rug lay just outside the front door. A spidery vine plant climbed up the local stone around the fireplace toward the window, on the long slow journey plants take toward the light. Everything was deliberate, considered, as though each item had also traveled and then arrived in its true place. The work of art was finished.

Her house mixed rugged western and Japanese-influenced modernism, a great angular open plan downstairs and an open second story with an interior balcony facing west over the sitting room and kitchen. Upstairs, the two bedrooms were only partially divided by a wall, and the shower looked east toward Notch Peak. Spaces flowed into each other, wood flowed into stone, and every room was full of books. The exposed structural members were old salvaged mine timbers, age-darkened beams so vast they were basically pine trees squared off, and not short or slender trees either. Jo Anne would describe the building of the place as a mock-epic that had lasted an alarmingly long time, much of the time of her romance with Joe, and was, if I’m not mistaken, unfinished at the time of his death.

I don’t know who Jo Anne was in her earlier phases, and when I finally saw a photograph of her in the 1980s with dark hair, I was a little shocked by the unrecognizable woman there. Who she had been as a young woman, as a mother to children and then those children grown up, as a woman caught up in a romance strong enough to break a marriage for I don’t know.

She had been many people along the way, but by my time she had found a philosophy—and, as far as I could tell, lived up to it—of kindness, of generosity of spirit, of careful listening, and even more careful judgment. She was loath to say anything bad about anyone and even had gracious terms for the greedy and powerful people she fought for years to defend the place she loved, amusing variations on “confused” and “wrongheaded.”

She had a light laugh and a host of airy expressions, in speech and in writing. When she said, “I love you,” as she often did when I arrived or departed or we finished a phone conversation, the words were delivered with a festive lilt. Most people say “I love you” as though they’re dropping something heavy, possibly sodden, at your feet, but her love flew up like a bird, or so her intonation suggested.

In 2002, she wrote me about an environmental benefit: “Totally against my rural, vegetative and penurious grain, I seem to be headed tomorrow for the fast lane of Las Vegas. . . . My local best friend, Margaret, has agreed to go along. She is a gala person, so this will be fun (as well as improbable).” Her style seemed to be a mix of the esprit de corps of the 1940s, which prized good cheer and lightheartedness, and the hard work she had done since, the work of making herself, of setting on a journey to become rather than just drifting along as most of us do.

She had made herself, which you do if you live long and intentionally, and made herself as someone whose kindness and steadfastness were notable. Maybe that’s how she came to seem like her hospitable house. She was not tall but had a straight back and strong arms and dressed with quiet style in jeans and white and blue shirts with the same few pieces of silver and mother-of-pearl jewelry over and over and one western bracelet intricately braided from horsehair. She was weathered like the wood of her house, creased from smiling.

[ 4. ]

You travel to get somewhere, and you travel for the sake of adventure, for the scenery, for being in motion, for discovery, for being uprooted and at large, that nice expression that seems to suggest that liberty is an enlargement of the self, that you grow as your scope does. But maybe the final art of travel is arrival, the end of the story that eludes so many of us who are afloat or adrift, who believe there should be, must be, something next.

In a way, everything is traveling: the planet revolving daily, orbiting the sun annually, the blood traveling within our veins, the ideas traveling within our minds. Maybe being still is how you turn your attention from the logistics of your own trajectory to the passage of all the other beings and their shadows. To arrive, then, is not about immobility but something else, perhaps confidence, clarity, satisfaction, attention.

Thinking of Jo Anne now she seems like an incarnation of the West or the ideal of the West: unflappable, self-reliant, vigorous, tenacious, resourceful, a lover of light and space and place and land, not only of people. But also like the Buddhist idea of a bodhisattva, a person who has devoted herself to the salvation of all beings, rather than self-salvation and disappearance from the realm of us mortals off into nirvana. It would have been easy to imagine the landscape she was in as fixed and unchanging, like the rocks themselves, but its fortunes were being shaped by people far away, and most of Jo Anne’s journeys in later life were to intervene in that process.

She won a great battle to protect her place and was at work on another at the time of her last journey. The former was the battle to defeat the MX missile, or rather to defeat the late-1970s plan to put long-range nuclear missiles on a circular railroad track that would go round and round eastern Nevada and western Utah, rotating two hundred or so nuclear bombs through 4,600 sites.

The mad notion behind this railroad to nowhere was that the missiles were serious enough menaces that the Soviets would be forced to target them, should the all-out nuclear armageddon both countries spent decades preparing for come to pass. The circular railroad track was akin to painting a target on the place. The deep desert was to become a national sacrifice area, a place that would be destroyed to save the rest of the country. The possibility of Soviet bombs wasn’t the only threat; construction of those bunkers and that railroad to nowhere would have ravaged large portions of the Great Basin and sucked up quantities of its precious water.

[ 5. ]

You set out on a political campaign as you would a journey into the unknown, unsure if and when and where you will arrive, with ideas about what you’d like but few of how you’ll get there and with whom. It’s a walk; you go step by step, and you learn along the way; the ground itself changes underneath you; and if you win, you’ve changed the world a little. Often you’ve changed yourself and your relationships, learned things, formed friendships (or made enemies), generated other movements or activists, or changed the benchmarks for what we can and may aspire to. Activism is full of peripheral achievements that are rarely measured. And outright victories that are soon forgotten—who now thinks of the bomb cemetery the deepest deserts of the West might have become?

Jo Anne became part of the leadership, helping to form organizations and serving on the board of Citizen Alert, the Nevada-based group that was founded to fight the MX, for almost three decades. The great house was a gathering place in which activists met and planned and coordinated to defeat the destruction of the place. She traveled to Ely to host the meeting she and Joe had organized with the locals one icy January day in 1980; eight hundred people showed up, a huge crowd for the sparsely populated region. She went to the nation’s capital to meet with the major environmental groups.

It’s hard to say what defeated the MX missile. The Mormon church eventually came out against it. Nevada senator Paul Laxalt finally came out against it. Jimmy Carter lost the 1980 presidential race to Ronald Reagan, and Laxalt, a Republican and a friend of Reagan’s, may have been the decisive power that convinced the Reagan administration to cancel the shell game in the desert. But it was grassroots activists like Jo Anne who brought the issue to the attention of the public and the people in power. Without them, in that case and so many others, the whole process might have gone forward without a hitch.

I joined the board of Citizen Alert in 1996, when its glory years of being a grassroots group fighting the MX and then facing Nevada’s myriad environmental problems (many due to the state’s huge military presence and nuclear issues) were waning. That’s how I got to know Jo Anne. For the next six years I saw her at meetings and retreats in Nevada, the first of which was in Austin, way out Highway 50 in the center of the state, a dry little town that once boomed so big from mining that every tree for dozens of miles around was cut down.

[ 6. ]

There’s a rhythm to traveling east or west across Nevada, a little like hitting waves in a boat, but these crests in the form of mountains come an hour apart. Once you cross over the Sierra Nevada, where the peaks scrape off the clouds and their moisture and create the rain shadow of the Great Basin, you enter the basin and range country, where a succession of north-south mountain ranges are separated by long valleys, many with few or no visible human inhabitants.

The silence, the space, the subtle variations between one grass and sagebrush basin and the next have their own beauty, one that has never received much praise. The mountains have been called sky islands, because moisture increases with altitude, and in the heights, trees grow, animals thrive, and species evolve in isolation from the next island across the sagebrush sea. Water is hidden in creeks in steep valleys, in inconspicuous springs, hot springs, and geysers. This regular landscape ends spectacularly in the range centered on Wheeler Peak and the surrounding landscape that became Great Basin National Park in the 1980s.

Those summer days on the road, I counted my wealth in how many homes I had to stay in en route, how much landscape I could drink up, how much pleasure there was in the way the road opened up and the world appeared, this mesa, that mountain growing closer and closer until you were driving up it and desert gave way to forest, heat to cloudy coolness, this little town, these mustangs running across the road, that river and its cottonwood groves. The places too became old friends.

I didn’t have a cell phone during the first several years, and even after I did I was entering vast signal-free zones where I could be truly alone on roads where you might not see another car for a long time. I would arrive at Jo Anne’s with a cooler full of produce from California’s superabundance, melons and greens and whatever was freshest back home, along with books and Chinese mooncakes or loaves of bread not available in the outback. Sometimes I’d call to take orders for coffee or fresh corn. I’d arrive; she’d pour wine or water or coffee, and we’d go sit on that ledge outside the bedrooms, and the shadows of the mountains at our back would travel their dozens of miles across Snake Valley again.

She would put me in her guest bedroom or the little apartment on the south side she and Joe built to live in while they worked on the big house. I went to Jo Anne’s to write the first chapters of my book A Field Guide to Getting Lost early in the millennium, late in the spring, and I would write and hike during the day, visit her in the evening to watch the light from upstairs. In that green oasis, more and more butterflies darted and hovered around the creek and its blossoms, and then time itself seemed to run backward as late storms arrived and it all snowed over. Eventually even Jo Anne’s yard and drive snowed up, and I drove five miles or so through the snow to the plowed highways and back home. She stayed.

She was fighting the Las Vegas water grab in those days, an attempt by what was for many years the fastest-growing city in the U.S. to round up enough water to keep its fountains and golf courses going no matter what. The plan was to put in a long pipeline that would suck out the groundwater that fed the springs, the seeps, the wetlands, the wildlife, and the ranches and turn eastern Nevada and a bit of western Utah into a dead zone. Jo Anne had taken on the battle with zeal, and liked to say it had reinvigorated her in her eighties. In 2004, she wrote me, “And intuitively I’ve felt like going for it, without any expectation of success, or even support. At the same time two other women from far-flung sections of the state are saying the same thing. What fun!”

[ 7. ]

The wrong kind of travel seized hold of me in recent years, work travel to cities and among strangers, trips in which I disgorged ideas rather than took them in. I didn’t drive across the Southwest nearly as much, and my summers lost their rhythm. When I managed to get out there, Jo Anne had more limited energy and would make it clear when it was time to leave her to herself. And then she began to fail.

In the fall of 2012, I tried to visit, but the weather and the window of time didn’t cooperate. My dear friend B Fulkerson kept me posted. The head of Nevada’s Progressive Leadership Alliance for the last twenty years, and before that the director of Citizen Alert, they had had their life changed by Jo Anne. She had recruited them in the 1980s, when they thought they were going to become a teacher, and their adult life sprang from that detour she offered them, with great benefits for the people and land of Nevada. B, a fourth-generation Nevadan, in turn changed my life when in 1990 they invited me into the heart of his home state. I’ve been a devotee of Nevada ever since.

In the spring of 2013, my brother David and I drove up from San Francisco to B’s Reno home, transferred our gear to B’s four-wheel-drive truck, and set out. We camped that night by an old reservoir a hundred miles down a dirt road and got to Jo Anne’s early the next afternoon. She was home as usual, a little more worn, smaller, more fragile, a little more scattered, but sparkling and delightful and welcoming. We sat with her downstairs eating berries and other California treats, but left the food I had brought to cook for dinner in my cooler; she preferred to go out and minimize the bustle.

We ate meat and potatoes at the rambling place ten miles down the road, and admired the photographs on the walls from the annual sheepherder’s gathering there. Afterward, B and David bunked in the little apartment, and I took up my old place in the bed just the other side of the wall from hers. In the morning we found out it was her eighty-eighth birthday and that we had celebrated it with her unwittingly. We told her we loved her, she said the same with her usual lilt, and then we went into the park, took the left fork of the road, wandered among the little linear garden of Baker Creek just as its lushness was springing up from winter and snow. The creek sang as its water fell over the small ledges, and B and I talked about old age and loss, and then we drove back to where we’d come from.

[ 8. ]

Like a life, a journey assumes a shape and a meaning that are only clear afterward, and like a journey, a life requires that you learn to let go of the plan when the actuality departs from it, to embrace what’s arriving, let go of what’s departing, to move forward and not get stuck. You can cover the same ground with entirely different purposes. Some people run away all their lives; some people search without finding; some people know where they’re headed and move toward goals, ideals, people; some in that subtlest of journeys move toward becoming who they are meant to be; some arrive.

In the summer she got pneumonia, and B sent me updates. In October, I was in another country with a friend who’d just had a baby when B wrote to me that Jo Anne had gone walking and not come back and there was a search effort on for her. I pictured the stony, dusty ground all around her house, the small old trees and slopes, and wished I was there among the searchers. The sheriff was called in, and forty people went out together looking for her, and continued looking for three more days. They say she had a faint smile on her face when they found her.

No one knows what she set out to do when she went walking from her house, but I think she may have gone to meet the fate that most of us run from. Not literally, and to say so is not to say that she was not confused, that it was not an accident. It’s just to say she walked all the way to the end of her journey and met the sunset on her feet. Few nowadays are granted such a complete arc, such a full day.