The War for the Imagination

I and we are wildlife whose natural habitat is libraries, when it comes to physical space, because they contain books in which minds roam free through time and space, encounter Dogen and Dante and Sappho and Black Elk and others long since gone, meet ideas and possibilities, meet each other in that deep way that AI can never replace, because when you read a work of literature you encounter another human being's struggles and successes in describing the world or their heart or a particular time and place in words, and that contact, even through the medium of black ink on white paper, even across continents and centuries, is human and humane.

We are wildlife because books freed us to reach beyond the particulars of time and place and self. And we are the Bay Area, which has been a liberatory place for writing, a place more out from under the shadow of Eurocentrism than the East Coast, a place where poetry broke free seventy years ago, a place that faces Asia, in a state that shares a border with Mexico. In what we now call California, which was a place of astonishingly linguistic and cultural diversity and creativity among its first peoples, and that too has been and is and will be at the heart of the stories and voices of this place. This place people came to as a refuge, from orthodoxies and conventions, a place to rethink what is possible, this place for liberation, as we stand here across the plaza from San Francisco City Hall, where the student movements of the 1960s began with a protest there against the repressions and witch hunts of the House UnAmerican Activities Committee in 1961, where the campaigns for marriage equality became public with that swoony spring of same-sex marriages twenty years ago.

I am of the Bay Area, though not born here; it was here I learned to read thanks to Mrs. San Felipe in first grade in Novato, over there on the unceded territory of the Coast Miwok; it was here that I have haunted libraries and bookstores since that immeasurable gift of literacy handed me the key to open the treasure-boxes that are books and feast on the contents within; it was here in San Francisco on the unceded lands of the Ramaytush Ohlone that I became a published writer more than forty years ago; it was here that my first books were published, by City Lights and then the Sierra Club, and later by University of California Press and Heyday Books.

It is here in this library that I have gathered the research materials for so many of my books, as well as finding books to read for pleasure. Thank you library, librarians. And while I come here for research materials, I recognize and respect the democratic mission of public libraries, to make knowledge available to all, to offer access to the internet for those who otherwise lack it, to provide a calm space in which to read and think, to welcome all comers, to trust us to walk out of the building with the world's greatest treasures and return them. To recognize knowledge, thoughtfulness, and imagination as well as equal access as central to democracy.

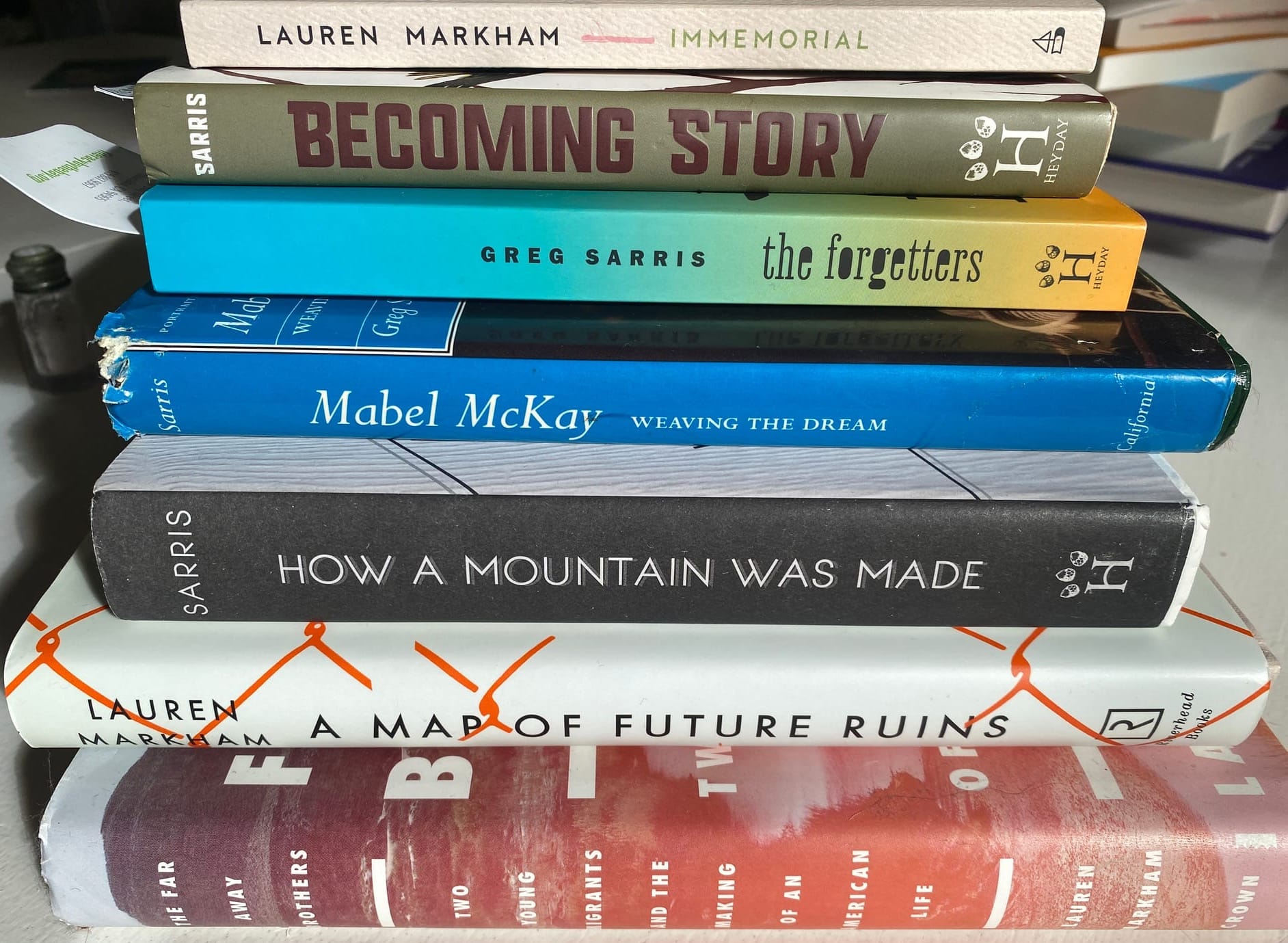

It's an honor to receive this lifetime achievement award from my community, and such an honor and a joy to be among family, friends, lovers of books, in this public library. And while I want to pay homage to how we meet each other and ideas and possibilities through books, I also want to salute the people with me in this room, because to be in the same room as my friends Greg Sarris, Lauren Markham, and City Lights's legendary book buyer Paul Yamazaki is to be in the presence of what has made the Bay Area a great place, an important place, a place that has given much to the world, that has opened up new and divergent stories of who we have been, are, and can be.

At the same time our city and our region and to an extent our world is being overrun by the sinister creations of Silicon Valley and the anti-democratic agenda of its oligarchs. This manichean struggle has always been part of this place, at least since the Spanish invaded. The Gold Rush enriched four merchants who built the transcontinental railroad's western half, invading the indigenous nations of the Great Plains, shrinking time and space themselves and making it possible to go around the world in eighty days; one of them, Leland Stanford, with his immense wealth achieved in part from fleecing the federal government, invading indigenous nations, and exploiting immigrant Chinese labor, founded Stanford University, from whose loins came Silicon Valley. (That marriage of money and power was central to my 2003 book River of Shadows: Eadweard Muybridge and the Technological Wild West.)

On the very land this building occupies now, the anti-Chinese Sandlot riots of 1877 were launched, which very nearly burned this city down in the subsequent rampages. While the rest of the country was convulsed by the closest thing we've ever had to a class war, here the rage against the elites was redirected by manipulative demagogues into racial hatred and scapegoating. Perhaps it's a partial answer to that hatred that the Asian Art Museum, the largest such museum in this country, stares down this site. The rest of the answer is up to all of us now in our defense of our immigrant and refugee kin and our antiracist commitments.

To spend so many years loving and exploring and writing about this place is to learn to trace the threads woven together in a tapestry of liberation and oppression, creation and destruction. For example, the Sierra Club was founded not far away from here on Montgomery Street in 1892, but its vision of what nature was and should be and how to protect it was racist when it came to writing Native people out of the picture. That representational genocide was a central subject of my second book Savage Dreams: A Journey into the Hidden Wars of the American West. The deeply flawed worldview of John Muir did protect some places from development, and it begat the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, which became Earthjustice, which just recently went to court and won a preliminary injunction against Alligator Alcatraz, on environmental grounds, in a suit to which the Miccousukee Tribe was party. I'm proud my friend Conchita Lozano-Batista, general counsel for Earthjustice, is here.

What this place will be, and what this country will be, is the subject of a battle right now, and I believe that books have a crucial place in it. They hold the records, the truths, the facts, in ways that cannot be forgotten, manipulated, or erased in ways that digital information can. Books, I once wrote in one of mine, are solitudes in which we meet, in which the reader in his deepest solitude meet the writer in her deepest solitude; they encourage the empathic imagination that arises from entering into lives other than our own, from expanding beyond the bounds of the self; they encourage the concentration and attention that makes us thoughtful in the most literal sense.

Hannah Arendt famously said, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exist.” We as readers and writers, as critics and publishers, as librarians and supporters of independent bookstores, are committed to making and defending those distinctions, in supporting the intelligence and informedness to be good at it. The battle against authoritarianism is fought in the streets, but also in the mind.

We can see in Trump's declaration of war on Chicago with a sordidly pretentious meme in which this sack of sad potatoes cast himself as the bloodthirsty lieutenant colonel in Apocalypse Now, in Vance's tweet gloating over the murder of a boatful of people whose mission was not clear, what the death of empathy looks like. And while I've said since 2017 that schadenfreude when it comes to the destroyers is sometimes only hope that the harm will stop, that underlying it is care for the vulnerable and the victimized, we need more than that. Not only do we need to oppose them; we need to be the opposite of them. In The Faraway Nearby I wrote, "Kindness, compassion, generosity are often talked about as though they’re purely emotional virtues, but they are also and maybe first of all imaginative ones," and that imagination can be fed and encouraged--or starved.

A great bygone San Franciscan, Diane DiPrima, once said, "the only war that matters is the war against the imagination." Against the imagination that has empathy for the refugee on the border, the child in Gaza, the prisoner, the homeless elder in the shelter, that can work to grasp the dimensions and impacts of the climate crisis and our eternal inseparability from nature, that can commit to the endlessly rewarding and demanding act of understanding. Before you harm a living being you have to fail to empathically embrace it; you have to close yourself off; wither your outreach to the world; murder your compassion.

If there is a war against the imagination, there is one for it, and I'm honored to be here with you all, on this side of it.

p.s. Saturday the Guardian published this essay of mine about the Epstein press conference and the larger implications. It too is about the failure of the empathic imagination and those who savage the principle that all people are created equal and endowed with certain inalienable rights.

Rape is a crime against democracy in the most immediate sense of equality between individuals and the premise that we’re all endowed with certain inalienable rights. Most rapists operate on the premise that they can not only overpower the victim physically, but can do so socially and legally. They count on a system that discounts the voices of victims and only too often cooperates in silencing them, through shame, intimidation, threats, discrediting, the obscene legal instrument known as a nondisclosure agreement and a system too often run by men for men at the expense of women and children. That is to say, rapists count on getting away with it because of a system that hands them power and steals it from their victims. They count on a silencing system. On profound inequality.

Which is what makes rape such a peculiar crime: it is the ritual enactment of the perpetrator’s power and the victim’s powerlessness, buttressed by the circumstances that puts and keeps each of them in those roles. It’s driven by the desire to use sexuality to cause physical and psychic injury, to dominate, to celebrate the rapist’s power and the victim’s powerlessness, to treat another human being as a person without rights, including the right to set boundaries, to say no and to speak up afterward. A society that perpetuates and protects this desire and arrangement is rape culture, and it’s been our culture throughout most of its existence.

Democracy, in this context, means a society and system in which everyone’s rights matter, everyone’s voice is heard and everyone is equal under the law. Rapists count on this not being true, but is has become more true over the past half century, thanks to feminism, and changed a lot more over the past dozen years, thanks to more feminism. There has been a shift toward equality of of voice, rights and support from the legal system, from arresting officers to investigations, judges and juries (who, thanks to feminism, are no longer exclusively male). It hasn’t changed enough, but it’s changed a lot, which is how a hundred survivors of Jeffrey Epstein’s rape club were able to gather with the support of Thomas Massie, a Republican congressperson from Kentucky, and Ro Khanna, a Democratic representative from California, on Wednesday morning to speak to the world about their experiences and demand justice.

The essay continues at the link: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2025/sep/06/epstein-files-rape-crime-trump