We Were Made for This

Twenty years ago, on August 29, 2005, a huge hurricane hit the Gulf Coast. New Orleans's levees failed, as had been predicted, and much of the city went underwater. Although the authorities had issued a mandatory evacuation order, they had provided no resources to the many who were too poor to evacuate. They were left behind. The levees broke, the city flooded with water polluted by sewage and by the oil refineries all around, the power went out, supplies were scarce. Almost immediately after the storm hit and the city flooded, mainstream news organizations and government leaders began cooking up stories about those mostly poor, mostly Black people who were left in the city--racist stories that they were marauding hordes, murderous gangs, rampaging looters.

Maureen Dowd of the New York Times wrote with confidence from afar that the city was "a snake pit of anarchy, death, looting, raping, marauding thugs, suffering innocents..." Far away in Britain, political columnist Timothy Garton Ash was convinced that “Katrina's big lesson is that the crust of civilisation on which we tread is always wafer thin. One tremor, and you've fallen through, scratching and gouging for your life like a wild dog." Louisiana Governor Blanco said she was sending troops, declaring "They have M-16s, and they’re locked and loaded..... I have one message for these hoodlums: These troops know how to shoot and kill, and they are more than willing to do so if necessary, and I expect they will.” That language and the beliefs behind it turned rescue into combat, victims into enemies.

We live and die by stories, are fed and freed by the good ones, trapped and sometimes quite literally killed by the bad ones or the people who believe them, even sometimes by ourselves when we believe them. The stories the powerful told about the stranded people of New Orleans were bad stories in two senses: they were extremely not true, and they justified violence and punitive measures against the people demonized as threats rather than recognized as victims. Who were, as you probably already know, mostly Black, mostly poor, including many elders and single mothers with small children.

Nevertheless, the mayor, police chief, governor, and almost every mainstream news outlet joined in credulously believing and amplifying untrue stories, and in obsessing about property relations, aka preventing petty theft, while grandmothers were dying. Thousands of people were stranded on freeway overpasses, rooftops, the Superdome arena, and other sites, and what was called theft was in many cases obtaining the equipment necessary for survival--food, water, diapers, medicine, clean clothes--when there was no electricity, no open stores, no way to use credit cards or get money from banks.

The fictional stories about savage mayhem had real consequences. The flooded city was essentially sealed off, and thousands were trapped in the hot, befouled, broken city. Across the Mississippi from New Orleans, the sheriff of Gretna and his men literally pointed guns at those who tried to walk across the bridge to dry land. The federal government prevented rescuers from entering the city. The police chief decided protecting retail goods was more important than people.

FEMA, the Federal Emergency Response Agency, had been rendered incompetent by nepotistic appointments and a right-wing government convinced that terrorism was the only threat that mattered. FEMA officials suspended search and rescue operations, claiming it was too dangerous, and the police shot at a significant number of unarmed Black people, maiming and killing some of them.

There is a story about human nature that serves authoritarianism well: the idea that we are either too feckless or too vicious to function in the absence of strong authority backed by the threat of violence. That our weak, chaotic nature requires them and their domination and brutality. Authoritarians love to tell stories of crime and depravity, usually about whoever is portrayed as the outsider, the intruder--nonwhite, non-Christian, non-straight, non-native people, stories in which harsh measures, suppression of freedom and dissent, are necessary to institute a kind of order that is in fact repression and forced homogeneity. We are seeing that now coming from the current administration, with its invasion of Los Angeles and then Washington D.C., its persecution of immigrants and anyone who resembles them.

But disasters tell us a different story about human nature, about who we really are, one that is profoundly important for everyday life. Because despite the grotesque stories and institutional panic, there was bumper to bumper boat traffic the morning after the storm hit, of people trying to launch their boats to see what they could do for the people of New Orleans. The flotilla was dubbed the Cajun Navy. The Cajun Navy has always served as a beautiful example for me of active hope. No one went there knowing for sure that they could save people, some must have worried about the reported chaos, but they went. They plunged into the utter unknown of a flooded, ruined, abandoned city.

Hundreds, maybe thousands, of people from as far away as Texas launched their fishing boats and small watercraft knowing they could not save everyone, and maybe they wouldn't save anyone, and they were risking their own safety in those filthy waters full of unseen snags. But they plunged into possible danger and definite uncertainty and saved many thousands, one or three or eleven at a time. Ever since, I have thought of the Cajun Navy when I hear that we can't save everything. We can't, but if we show up and take risks we might help someone. The fact that we cannot save everything does not mean we cannot save anything, and everything and everyone we can save is worth saving.

But not only the Cajun Navy was amazing in that disaster: many of the stranded self-organized into communities for survival, a dozen or a few dozen taking shelter in a school or a mall and figuring out how to take care of each other. The daughter of a hospital worker, who took shelter in that hospital recalled, “We were trapped like animals, but I saw the greatest humanity I'd ever seen from the most unlikely places.” Online thousands of people offered to open their homes to the evacuees, sight unseen, despite the grotesque stories. In the months and years afterward, one of the greatest volunteer efforts ever marshalled in this country arose, tens of thousands of people, young anarchists to old Mennonites, showing up to serve in soup kitchens, gut and rebuild houses, open clinics. Some of those efforts lasted years.

What was true of the majority in Hurricane Katrina is true of most of us in nearly every disaster: we are courageous, we are generous, we are altruistic, we rescue each other, take care of each other, improvise the conditions of survival for and with each other. Institutional authority is usually overwhelmed or irrelevant or panicking, but ordinary people act with grace and solidarity. I wrote a book about who we are in these moments called A Paradise Built in Hell.

Disasters are hell. But the way people respond, the experiences they have, the way they show up for each other can create a sort of paradise of generosity, solidarity, courage, immediacy, purposefulness. I was prompted to write the book by the way that destructive stories led to suffering and death in Katrina, by the importance of knowing who we are in these emergencies, and maybe who we are in the deepest sense, underneath it all, or potentially, all the time.

The astonishing thing about disasters isn't that people behave well, respond effectively, rise to the occasion. It's that some of us, a lot of us, find in these urgent moments the sense of meaning, purpose, connection, and immediacy that are often missing from contemporary life, and in finding that they find a deep joy in the most unlikely places. Over and over and over, in the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, in the London Blitz, in the Mexico City earthquake of 1985, in the Lower Manhattan response to 9/11, in Katrina. In more recent years, in community response to wildfire and flood.

I wrote that book because we are entering the age of climate chaos, or rather have entered it, an age of more disasters and more dangerous/destructive ones. I bring it up now because we are in another kind of disaster, and I see both the hell of authoritarianism trying to strip us of so much that matters, and I see the paradise of an engaged civil society responding to defend each other, defend values and principles, nature, science and truth. The theories of human nature underlying each position are diametrically opposed.

It is a difficult and scary time, but I believe we were made for this.

[This was written as a talk for Upaya Zen Center, and so here Buddhism enters in, and stays in for the rest of the essay/talk]

I wrote in A Paradise Built in Hell, "Indeed, disaster could be called a crash course in Buddhist principles of compassion for all beings, of nonattachment, of the illusion of one’s sense of separateness, of being fully present, of awareness of ephemerality, and of fearlessness or at least aplomb in the face of uncertainty. You can reverse that to say that religion is one of the ways crafted to achieve some of disaster’s fruits without its damage and loss. That state of clarity, bravery, altruism, and ease with the dangers and uncertainties of the world is hard-won through mental and emotional effort but sometimes delivered suddenly, as a gift amid horrific loss, in disaster."

For most, this other state of existence during disaster is fleeting; most people go back to some version of the life they were living before, the assumptions they operated on before. A minority change their lives profoundly. I think of a disaster as shaking people awake to who they can be and what they value most. That joy comes from finding out who we really are and what we really value. It comes from the fact that what we want most deeply is meaning and connection, even after lifetimes of being told that we just want to be pretty, and rich, and safe, and amused. That joy comes from finding our deepest selves and finding each other in a deep way.

So it shakes us awake but then we fall back asleep, fall into this other version of ourselves. The question I was left with is how do we stay awake? There are many answers and of course many people whose lives are awake to the search for meaning, purpose, and connection. One answer for awakening is Buddhism. To be clear, I'm a very primitive Buddhist, but also someone who loves Buddhism a lot not least because I think it proposes we actually have quite a robust self capable of great generosity, compassion, engagement, action on behalf of others, that somewhere deep down we have Buddha nature no matter how sad or confused or exhausted we may feel. And that we can wake up.

Buddhism as I understand or maybe misunderstand it is a constant invitation to be our biggest self, biggest in the sense of not separate from the rest of creation but also biggest in the sense of what we're capable of. We are in a global emergency with the climate crisis, the crisis of the technological invasion of consciousness, community, and culture, and the authoritarian crisis. We need our biggest selves for the emergency we're in. The good news is that we have them, but whether or not these selves are available and imaginable is, to some extent, a matter of what stories we tell and listen to and take in as our instructions on how to be.

I wrote somewhere that every crisis is in part a storytelling crisis and right now we're in a world in which we have an enormous array of stories to choose from

Roshi Joan Halifax reminded me recently that Buddhist practice offers not just better stories about who we are and can be, though we get those. We get the ability to pause our stories, to quiet down so we sit without the noise, be it lullaby or howl, of the stories we tell ourselves, to maybe glimpse things as they are without that overlay of interpretation and projection.

From that we learn that we are in fact the tellers of these stories, that we have great agency, including that ability to stop telling that particular story, or any story, maybe to notice what the story does, whether it helps or hinders, to change stories, to get off the runaway horse of a bad story or even a really fun story that inculcates obliviousness or righteousness or covetousness. I remember who I was before I wandered into San Francisco Zen Center in 2001, how I didn't even know that those loop tapes that overwhelmed me were stories, that I was the author of them, that I could recognize them, pause them, rewrite them. I didn't distinguish the reality of the situation from the story I couldn't stop telling myself about it, stirring the pot, over and over.

I mentioned that I'm a backward and bad Buddhist, so so I'm going to start from something almost anyone who's come to a dharma talk is probably familiar with, and I'm not even going into all four lines of the Bodhisattva vow.

Just the first: beings are numberless; I vow to liberate them.

What a wild thing, to vow to keep coming back, lifetime after lifetime, to get dirty, to keep working, to toil on behalf of all those numberless beings. To be an eternal Cajun Navy for hearts and souls, for lives and possibilities, returning again and again to see what can be done. It's audacious in its ambition and it comes from a sense of great strength, fortitude, resoluteness, from a commitment to stay, as Donna Haraway put it, with the trouble. I love that.

This version asks a lot of us, but it gives us a lot: it gives us our biggest versions of ourselves. It pictures us as extremely powerful, extremely generous, extremely capable, while many other stories that bombard us tell us we're fragile, we're weak, we need to marshall all our resources to take care of ourselves alone. Stories that tell us what we seek is only personal and private satisfaction and security, meaning comfort, ease, affluence, and ever so much avoidance. That we should look to other people for what we can get from them, what they owe us, view ourselves as clusters of needs lurching down the road.

Be careful of the stories on offer; test them for who they tell you you can be and we can be. Look for the liberatory ones, the ones that open doors and take you through the gates, not the ones that slam them. The ones that invite you to expand, not contract, to expand in care, in awareness, in connection.

beings are numberless; I vow to liberate them.

It is an astonishing and in all practical secular one-lifetime terms an impossible commitment! It's also a vow, and my assignment here was to talk about hope and I think hope is itself a kind of vow or a cousin of vows. "Hope is a discipline" prison abolitionist Mariame Kaba famously declared. Hope I have long argued, is not an emotion; it is a commitment to not give up, to keep looking for possibilities, to remain resolute in the face of uncertainty and even danger and devastation, to remember we make the future in the present. Hope is for troubled times, not serene ones; you can remain hopeful while mourning or raging or just feeling exhausted. Many have before us. Just to be a resident of the United States is to live in a country where enslaved Black people, colonized Native American people did not give up over centuries of oppression.

Hope says, this transformation might be possible, and active hope commits to realizing it: that's a vow. If hope feels too far a reach for you right now, if it feels like too much attachment to outcome, I offer resoluteness, what you can be in the moment, how you can stick to and stand for your principles.

Usually when I talk about hope I talk about history and possibility, about how the world got changed for the better, about the visionary organizers, the radical communities, the movements and insurrections that over and over and over again campaigned and won the protection of a river, a mountain, a forest, a region, a species, an oppressed population. But today I'm doing something different, because I think a lot of despair comes not from the political realities, but from the sense of self we get from the dominant stories of our society.

I've been thinking about capitalism a lot this summer, about capitalism as a story and an operating system, about how its basic principle is to take as much as possible and give as little as possible, and how it is only too easy to internalize it as a way to approach everything, to make everything into a business, to make your heart into a cash register, to get stingy, to see giving as losing and getting as winning, to make giving as little as possible the goal. To believe that the world runs on competition, and that you're on your own and everyone else is a competitor, a rival, an enemy. It's a dismal, impoverished version of who you and we are.

In the effort to impoverish others you impoverish yourself. If you internalize it, even if you're a billionaire you feel poor, you need to keep getting, to cut off giving wherever you see it. You might be the richest man in the world and in the name of efficiency, the Department of Government Efficiency, you might cut off aid to starving children, might dismantle an organization that feeds the hungry and cures the sick. The medical journal the Lancet estimated that DOGE's dismantling of USAID could result in more than fourteen million deaths, a third of them children, by 2030.

We absolutely can afford to feed them all, to house all the unhoused, to take care of everyone and everything, including the earth herself, to be bodhisattvas in everyday life, in our politics, in the distribution of resources, including the renewable resources of care and attention and solidarity. But capitalism runs on scarcity, manufactured scarcity, so while there is no actual absolute shortage of food or housing or anything else, distribution systems cut out a lot of people from the essentials for survival, let alone a good life.

And this sense of scarcity can transfer from the material to the matters of the heart. While there is a finite supply of material stuff, there is no limit to the stuff of the spirit you may have a finite number of hats or dollars or donuts, but you do not have a finite amount of love or kindness or words of encouragement, and giving the latter away increases the supply for everyone. So beware scarcity stories.

In New Orleans very shortly after Katrina struck, a former Black Panther, Malik Rahim, and a few others formed a relief group they named Common Ground and chose as their slogan “solidarity not charity,” a phrase inspired by the Uruguayan writer Eduardo Galeano’s statement “I don’t believe in charity. I believe in solidarity. Charity is so vertical. It goes from the top to the bottom. Solidarity is horizontal. It respects the other person.”

We often talk about mutual aid as though it's akin to gift exchange, but in actuality, it’s most often a one-way flow of goods and services, the unimpacted giving to the impacted. I learned from the solidarity work with the Auntie Sewing Squad I joined in the pandemic that what is mutual in mutual aid is not the goods and services that are given, but the underlying belief that we are mutual, we are not separate, we have a common destiny. It is a deep belief in and commitment to nonseparation, it operates on the premise that my well-being is inseparable from yours and that, in caring for yours, I care for myself and, more than that, for the larger whole that is us, because we are in this together.

That is, we are not mutual because of the provision of aid; we aid each other because we are already mutual.

What we do in the world begins with who we are and who we want to be, what we believe we are capable of, and what we believe is possible. Even in the worst circumstances, people retain some forms of power, the power to decide how they will conduct themselves in the choices that remain to them, and that includes the power of our words and our worldviews. Viktor Frankl, the Jewish psychiatrist who survived the Nazi death camp at Auschwitz, wrote, “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” He wrote in Man's Search for Meaning that what he learned from Auschwitz is that our deepest need is for meaning. Which comes in large part from choosing to live a meaningful life, from choosing to do what is most meaningful. Which means that what we see as giving, as in vowing to liberate all beings, gives us what we need most deeply. What is missing from so many stories is that we need to give.

When I wrote A Paradise Built in Hell, I drew deeply on the work of disaster sociologists, whose on-the-ground research contrasted dramatically with the grim version of human nature in disaster movies, the minds of politicians in actual disasters, and a lot of mainstream news coverage of disasters at least up to the Haitian earthquake of 2010. One thing they talk about is disaster convergence, the desire to help, to show up, to give, to care that sometimes means so many people show up they jam the relief work. The Cajun Navy was one example; in almost every disaster people create the community kitchens, the relief projects, reach out, offer help. In the current disaster, I see so many people stepping forward to protect people from persecution, from deportation, the loss of rights, stepping forward to protect the land and waters, the forests and national parks, the climate and the truth.

When we are generous, we give ourselves the gift of our most generous selves; when we are compassionate, we give ourselves the gift of our most compassionate selves; when we are brave, we give ourselves the gift of our most courageous selves. In giving to others, in working toward the liberation of all beings, we make the best version of ourselves, a version that cannot be made any other way, a gift we can receive only by giving. To the others who are inseparable from the largest version of ourselves.

We want to give, to share, to connect, to relieve suffering, to liberate all beings; doing so gives us meaning, purpose, lets us be our largest, most heroic selves.

We were made for this work, and when we do it we discover who we truly are.

p.s. The video of the talk and larger program at Upaya with Roshi Joan Halifax and Dainin Wendy Lau is at this link. (You might have to register, which is free, if you choose.)

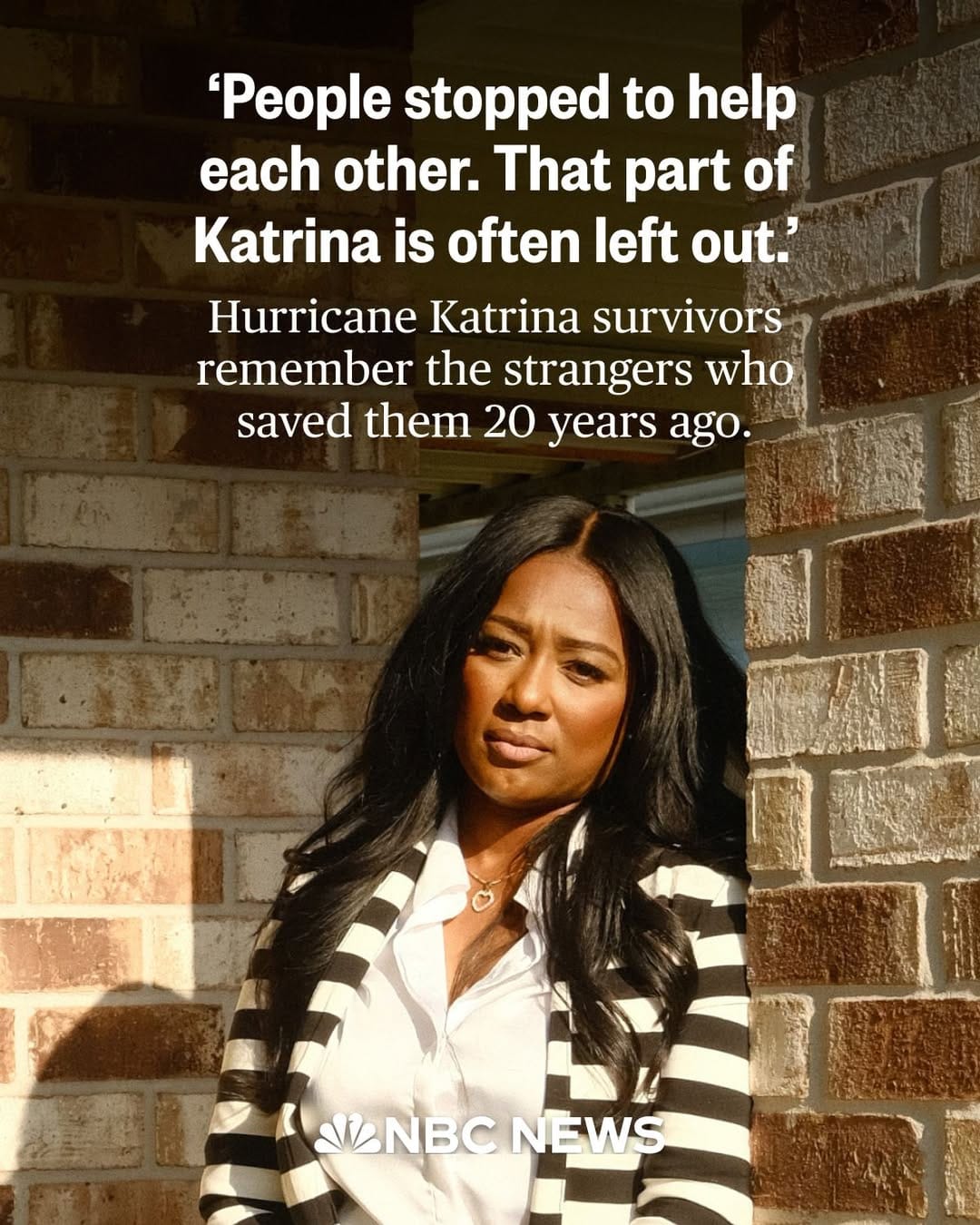

The pictured woman who was rescued by canoe tells her story here: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/hurricane-katrina-20-anniversary-survivors-compassion-new-orleans-rcna224874