When Love Thy Neighbor Is a Cry of Resistance

Today marks one full year for this newsletter, and here's the 77th post (I thought once a week was going to be a lot, but there's so much going on I wrote almost 1.5 times a week over the past year). I'm so grateful to all of you who subscribed and I hope you'll stick around for whatever this next year brings us and prompts me to write. There is so much to say – the constant emergencies and eruptions of criminality have kept me from composing a lot of the less urgent essays I might have written in an era of less volcanic news, less catastrophic politics.

I don't think we'll get to peace and stability anytime soon, but I do believe they are losing, if thrashing violently on the way down (I cited better authorities than me on that question of losing in the essay Weak Violence, Strong Peace). In the most practical sense, the open cruelty and corruption, the lies and destruction, are driving people into the arms of the opposition (may we not drive them away ourselves).

And they are losing the culture wars, though that's not news. Last night two of this country's most successful musicians spoke up: Bad Bunny said "stop ICE" and Billie Eilish said "fuck ICE" while accepting awards at the Grammies, to enthusiastic applause. Yesterday the Trump-controlled Kennedy Center announced it's closed for two years – to cover up that almost no one wants to perform at or attend the corrupted, debased institution Trump smeared his name on. The cancellations have come one after the other. Culture is on our side. Michael Jochum writes, "the fact that Bad Bunny has been chosen to perform the Super Bowl halftime show feels less like a booking decision and more like a cultural stress test. And judging by the early howling from the usual corners, the test is already breaking them. Because nothing terrifies self-styled 'patriots' more than a brown man who is wildly successful, beautifully androgynous, politically awake, and utterly uninterested in kissing the ring." Bruce Springsteen's anthem "Streets of Minneapolis" hit the top of the charts internationally, and he just performed onstage there with a fellow musician holding an "arrest the president" sign. Athletes, clergy, artists are all coming out against the administration. Yesterday's state senate election in a Texas district Trump won by 17 points was won by fourteen points – a 30-point shift– by a Democrat who was outspent twenty to one.

I'm in Costa Rica doing a little teaching with my friends Wendy Lau and Roshi Joan Halifax, abbess of Upaya Zen Center. Yesterday Costa Rica's own Christiana Figueres was supposed to do a zoom event with Roshi but got delayed by a windstorm, Roshi asked me to step in, and I wrote the following before we went live. I was able to do so quickly because it's a sketch-summary of my forthcoming book, The Beginning Comes After the End: Notes on a World of Change.

You can see the video here as part of the series of socially engaged talks Upaya Zen Center has organized and will share online as live zoom events and then videos sign up (for free or by donation) for the whole series here. Christiana, who will forever be my hero for leading the 2015 Paris climate talks to their successful conclusion in the Paris Climate Treaty, did come on in the last five minutes, the wind whipping her hair, and she was magnificent.

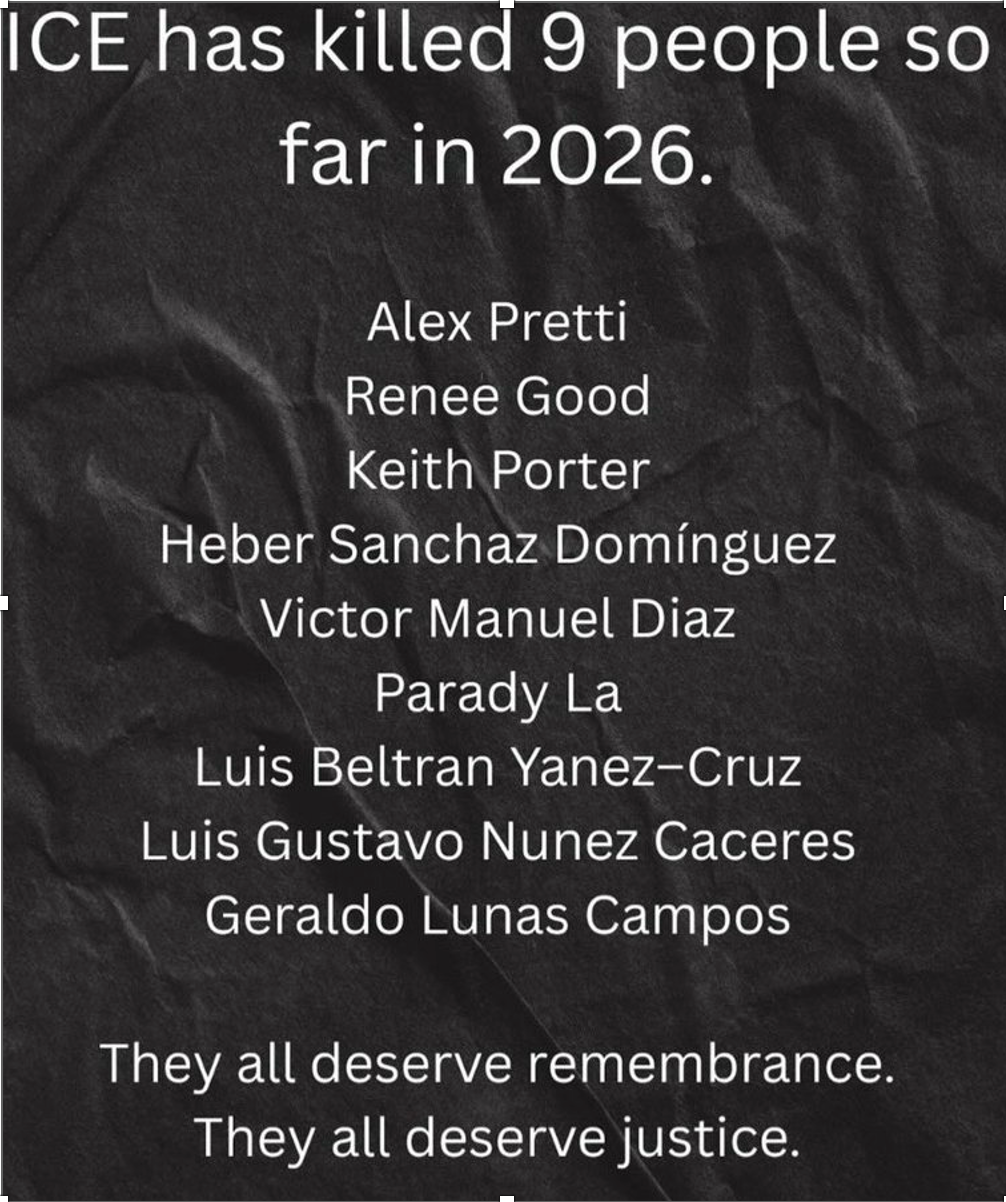

Roshi began the session by saying, We are in a time of extreme rupture. In the midst, solidarity and recollection are essential. Let us take a moment to remember the nine people ICE has killed so far in 2026.

When fear fragments us and the narrative of individualism has paved the way for authoritarianism, how do we measure ourselves not by what we fear or exclude, but by our capacity for connection and compassion?

The measure of our humanity is not found in isolation but in relationship. Not in dominance but in solidarity. Not in what we possess but in how we care. Not in our ability to other and objectify, but in our courage to recognize that "humans are not the enemy. It's the suffering from delusion, fear, and hatred that takes over and possesses us.

That's her (and if engaged Buddhism speaks to you, Upaya has a treasure trove of online talks and classes as well as in-person stuff if you happen to be near Santa Fe).

Here's me:

At the very heart of almost all our crises is a conflict between two worldviews, the worldview in which everything is connected and the world of isolated individualism, of social darwinism and the war of each against each. I call the latter the ideology of isolation.

This is at the heart of the opposition to climate action – acting on climate requires first of all recognition that everything is connected. That truth is offensive and threatening to this worldview which would like to believe in the unimpeded freedom of the elite individual to act without impediment or consideration, be it a rich man in his jet, a landowner to clearcut her forest, or a fossil fuel corporation to produce and promote this destructive material. They endeavor to sever cause from effect, the to deny that the burning of fossil fuel leads to the buildup of methane and carbon dioxide in the upper atmosphere, thickening the planet's insulating blanket and generating climate chaos.

Really the contemporary right would like to divorce cause and effect from everything. Theirs is an anti-systemic worldview in which they deny that, for example, poverty and poor health are very often the result of how the system is organized rather than personal failure, so they preach personal responsibility while denying collective responsibility and their own responsibilities, deny the collective overall. Margaret Thatcher famously said "there is no such thing as society," but we now know that societies exist even in the absence of human beings as forest ecosystems, ocean ecosystems. And the facts of climate change do threaten them directly by saying that what we do and don't do must be done in cooperation and coordination with all the rest of humanity in the service of all life on earth.

But this ideology goes beyond separating humans and our actions from nature; as you can see in the current US government, it wants to segregate us through a hierarchy of inequality, in which straight white Christian men are at the top, and in which women are separate from men and don't deserve the same rights, immigrants from US born, white from nonwhite, Christian from nonChristian.

It is a sad and lonely worldview and one whose most devout believers often seem miserable, angry, and eager to punish and harm. They have in recent years even directly attacked the idea and value of empathy. The word empathy literally means feeling into, the imaginative extension of the self into the other. I believe that this feeling at its best, as compassion, extends the boundaries of the self, literally makes you bigger as it makes you more connected; the intention of feeling compassion is the intention of expanding and relating and connecting. Its opposite withers you into the smallest version of yourself, a hard knot of ungiving. It robs you of the wealth of relationship; from that comes the sense of poverty and the insatiable hunger for more of our billionaires.

Adam Serwer wrote a beautiful essay in the Atlantic last week in which he pointed out that the ideology-of-isolation white nationalists in the government, including JD Vance, argue that you cannot have social cohesion without social homogeneity, which is one of their justifications for the evil and impossible pursuit of a white America that never did and never will exist. What is happening in Minneapolis, he notes there and in a podcast interview I listened to, undermines their worldview andtheir strategy, which seems to have been premised on the assumption that people would be selfish and fearful in the face of these pogroms.

Instead thousands upon thousands of white people are demonstrating that social cohesion exists in racial and cultural diversity so powerfully that people are willing to risk their lives, even after two of them lost their lives, to stand up for and seek to defend their Hmong and Somali and Latino neighbors, to protect them, bring them food, prevent or at least document their arrests, drive their children to school. It is one of the greatest examples of solidarity I have ever witnessed, and versions of it are likewise happening in New Orleans and many other places. This is a heroic age (and brings up for me Bertolt Brecht's famous "pity the nation that needs a hero," though this is not one hero but countless thousands). May we remember who we are capable of being when this crisis subsides.

At the very heart of the conflict raging in the United States is a conflict about human nature, a deep moral and philosophical conflict. I believe the isolationists will lose in the long run because they are not only out of step with the majority but they are out of step with reality and because theirs is an impoverished version of who we can be, walking away from the possibilities of love and joy and the sense of abundance and connection from which generosity springs.

In the opposite of the ideology of isolation, we recognize that everything is connected. That is the first lesson that nature teaches if we listen, if we learn, though capitalism and related systems of alienation and objectification taught us all to forget, ignore, or deny it. Nevertheless this cosmology of interconnection has grown more powerful and influential over the past several decades, thanks to many forces seen as separate but that all move us in the same direction: antiracism and feminism which reject discrimination, inequality, and exclusion; gay rights which insisted that gender does not narrowly define who we can be and who and how we can love and become beloved, become family; environmental activism that charts how damage moves downwind, downstream, how sabotaging one piece of an ecosystem affects the whole. The past two hundred years have expanded the idea of universal human rights and equality through revolutions but also through cultural shifts, which themselves can amount to slowmoving, incremental, subtle, and therefore too-often unnoticed revolutions that manifest in a thousand small ways.

At least as important is the resurgent power of indigenous worldviews, especially in the Americas, because although indigenous North, Central, and South Americans have wildly diverse cultures and societies, most of them insist on the inseparability of humans from nature, on interconnection, and on our role as stewards of nature. In the white world we often talk about responsibility but I prefer what Robin Wall Kimmerer, author of Braiding Sweetgrass, calls reciprocity. Responsibility sounds dismally dutiful, but reciprocity begins by recognizing that nature has given so much and therefore responds with gratitude and love, which makes the work not just giving, but giving back, a beautiful and natural response to abundance. (You can contrast that with the sense of scarcity and the manufacture of scarcity that underwrites capitalism's logic.)

Since the early 1990s indigenous people have become far more powerful, visible, taken leadership roles in the global climate movement and become hugely influential on the thinking of us settler-colonialists, first of all by correcting the story that we used to tell that culture and nature were somehow inherently at odds with each other, that human beings were inherently destructive. It has been a great revolution that I have been watching with joy, wonder, and exhilaration since the early 1990s. I talked about the expansion of the idea of rights and equality; the rights of nature is the next phase unfolding across the globe, from Peru and Colombia to Canada and New Zealand. Indigenous peoples of the Colorado River are seeking personhood for this exploited, exhausted river right now.

But this cosmology of connection comes from many directions. As Roshi Joan Halifax knows from lived experience, since the late 1950s and 1960s, Buddhism has come to the West in a big way and brought us many visions of interconnection – Thich Nhat Hanh's word "interbeing" is one description; dependent co-arising another, and compassion for all beings and the Boddhisattva vow to liberate all beings one of the central tenets of Mahayana Buddhism.

But that's not all. Contemporary biological sciences, from planetary ecology to botany, zoology, and neuroscience, have documented that we are all in dependent co-arising, that we are all part of systems and relationships, that each of us is not so much an individual but a node on a network, a plural being whose body is made up of billions of microorganisms as well as what we call human. There's a wonderful new field of biology called processual biology that looks at the world as made up of processes rather than objects, as phenomena forever flowing and changing and thereby exchanging with each other and changing into each other. It proposes that it is more useful and accurate to think of ourselves and most of what we call things as events.

After all you yourself in this very moment live by taking gulps of the sky into your lungs and could not last long without taking in that most gloriously fluctuating of all things, water, and devouring other forms of life, and other things come out of you, be they poems or babies or political contributions. Buddhism gives us Indra's net, a vision of an infinite net whose every nexus contains a jewel reflecting every other jewel; science gives us another version of that world of systems, connections, and relations.

For the survival of our democracy and our planet, understanding that interconnectedness, that capacity to relate and the abundance, joy, love that spring from it, are no longer abstract topics but an urgent political matter.

Thank you everyone. Onward to year two of Meditations in an Emergency.

p.s. This book, coming out in March, of which Donna Seaman at Booklist says: "In this remarkably lucid and fluent chronicle of social change over the last six decades or so, the course of her lifetime, she traces profound shifts in perceptions and convictions regarding race, gender, equality, and the environment. Confirming that we’re in the midst of a massive backlash as the right attempts to undo everything from the promise of renewable energy to efforts at achieving diversity, equity, and inclusion, Solnit argues that this reaction is due to already profound and ultimately unstoppable societal transformations. She delves into the Black civil rights, feminist, and LGBTQ+ movements, the rise in Indigenous leadership, especially in conservation, and paradigm-altering scientific discoveries, illuminating these pursuits of justice via profiles of trailblazers and accounts of her own experiences. The through line here is the recognition that everything and all of us are interconnected. Solnit’s holistic anatomy of the dynamics of change is precise, compelling, and deeply clarifying. Continued vigilance and action are required to protect human rights and the living world, and Solnit offers encouragement: “it is easier to see the old world dying than the new world being born. But beginnings are what come after endings.”"